Contents:

1. Introduction to LOOP

2. FOX system project introduction: Please join us in planning a virtual center for the study of placental failure, including stillbirth. Add your thoughts and potential contribution.

3. An introduction to dynamic system modeling: This is section is from my notes on a published textbook on dynamic modeling for living systems. If you want to join me in this effort, please do with comments or questions.

4. Pathology cases report #1: A placenta with a long umbilical cord, marginal insertion, and chorionic surface thrombi. Some single cases may not be publishable, but their very existence begs interpretation and engenders hypotheses. Please contribute such cases and their analysis!

5. Narrative review: The significance of umbilical cord length. I am reviewing and updating some topics in obstetric pathology from my blog (www.obstetricalpathology.com) and would like to share them here. If you have similar chapter type publications, feel free to also share them here.

I have not confirmed with a lawyer, but publication in a private electronic communication is usually considered an exclusion for prior publication.

**********************************************************************************

Introduction to Letters on Obstetrical Pathology, LOOP

With a nod to the early Letters to the Royal Society, I want to create an informal communication forum with continuity for discussions, with essays expressing ideas and with a place to suggest research and find collaborators. This is not to be a formal peer reviewed, indexed medical journal, but a mix of brainstorming sessions, and after-hours discussions. My own projected contributions are 1) share interesting cases: One goal of sharing cases is to find out if any others are making the same observations. It was at SPP meetings that the first case of massive chronic intervillositis, of mesenchymal dysplasia, and of umbilical cord ulcer were presented, and these individual cases led to collaborative publication of series of cases and the establishment of a new entity. I also want to explore case material as the basis of hypothesis formation, abductive reasoning. 2) I am looking for collaborators for a long-term exploration of applying dynamic system analysis to failures of fetal oxygenation and want to embed a newsletter about this potential research program. 3) I want to update the short topic reviews on my current website www.obstetricalpathology.com, and my previous website (both were written before the Amsterdam conference). I am hoping these reviews will stimulate discussion about topics in obstetrical pathology.

This project will only succeed if you, pathologists, obstetricians, neonatologists, basic scientists, engineers and other interested individuals, contribute your ideas.

Looking forward to your input,

Bob Bendon, MD

**********************************************************************************

Introduction of the Fetal Oxygenation System (FOXS) project, and an invitation to participate.

For those who are still participating in this project, and those who are interested in joining, we weren’t ready for the stillbirth centers RFA Deadline of Nov1, but we will persist. The goal is to develop a linked set of physical and virtual centers participating in the overall program comprised of Individuals and institutions across the world. Crazy ambitious, but the newsletter will start the process.

The project is broader than just stillbirth. Most stillbirth is ultimately an acute failure to provide enough oxygen to sustain fetal life. This system failure to provide oxygen also underlies perinatal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, an etiology of cerebral palsy, and like stillbirth, has not decreased its incidence over the last decades. The third major obstetrical complication due to a loss of fetal oxygenation is the increase in Cesarean section based on non-reassuring fetal heart tones. This project sees all three complications as system failure of the maternal-placental-fetal oxygenation system. The motive for this program is the parents who have suffered the stillbirths, cerebral palsy, and complications of Cesarean sections.

Please send comments (bendonrw2@upmc.edu) : This program outline is subject to change depending on other more expert input.

The program has 6 major project areas, expressed as aims.

AIM 1 Maternal-Placental-Fetal Dynamics System (MAP FEDS, pronounced map feeds) project:

To apply dynamic system modeling to develop new quantitative insights into how short-term events can lead to a tipping point of non-stable decreasing of oxygen transfer to the fetus based on a description of the state of the system based on risk factors and fetal monitoring. This part of the project Is the

AIM 2 Measurement of Dynamic Functioning (MODYF) project:

To develop new anatomic pathology methods to understand (in retrospect) how the placental anatomy dynamically effects fetal oxygen transfer, and to extract more information from the autopsy of the stillborn infant about the acute events leading to death. For the placenta: 1) Measuring the anatomic factors of impedance to fetal blood flow: 2) Determining the extraction rate of oxygen from the flow of maternal blood; and 3) measuring placental anatomy component to impedance of intervillous blood flow. For the infant:1) measuring the state of circulatory function and extent of stress response in fetal organs.

AIM 3 Multi-Access Patient database project (MAPS data) project:

To develop a data system that maintains files on individual patients and can access from large databases quantities of varied formatted data as FHR tracings, ultrasound studies, clinical history, MRI images, and digital pathology slides for each patient, and process the data for the needs of the system model in Aim 1.

AIM 4 Technology and Protocols project, (TAP) project:

To develop patient monitoring protocols and technology that best measure the critical state variables and parameters that identify the onset of changes in the equilibrium points of the FOXYS and predict the time to a tipping point leading to fetal deoxygenation.

AIM 5 Patient Outreach and Care, (POC) project:

To maximize the care of the patients in mutually beneficial ways: recruitment of patients with high risk, providing care in labor and delivery, meeting the needs for access to patient care, obtaining an optimum clinical history, creating better communication after a placental failure complication and creating more effective follow up and therapy.

AIM 6 Links of Causation Knowledge (LOCK) project:

To utilize advanced molecular and genetic technologies to identify other variables that can be incorporated into the systems model and may also directly link to pharmaceutical pathways of value in modifying the system stability.

*************************************************************************************

Introduction to the proposed application of dynamic modeling to the problem of stillbirth as the first aim of the FOXS project: Maternal-Placental-Fetal Dynamics System (MAP FED)

I and a small group of colleagues want to assemble a virtual group interested in applying dynamic system modeling to the problem of fetal hypoxia including stillbirth and perinatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. The idea of using system dynamics to discover more about causation of stillbirth follows from several experiences. First, neither risk factors, nor prenatal monitoring, can predict when a stillbirth will occur which suggests that there may be acute factors that lead to a tipping point. Likely evidence of a tipping point is demonstrated in the fetal heart rate tracing, “the staircase to death” that could be a positive feedback loop, in which cardiac hypoxia leads to decreased output/heart rate that then decreases placental return of oxygen which then leads to even greater cardiac hypoxia and acidosis leading to further decreasing heart rate with less output and hence even less placental perfusion, until death ensues. The unexplained anatomic mechanism of many stillbirths, even after autopsy and placental examination, suggests that multiple insults could be leading to a tipping point. Dynamic systems can predict the onset of unstable equilibrium in a system.

As part of the systems approach is the need for precise quantitation of key variables and parameters. This is especially evident in the placenta where lesions can remove portions of functioning placenta, as occurs in multiple infarctions, and death can occur after on additional acute infarction. Observation of abruptions shows that a 50% abruption can lead to lethal progressive cardiac hypoxia evidenced by findings of fetal heart failure, while a near acute abruption shows immediate asphyxia with findings of fetal gasping. The amount of functioning placenta is a key parameter. One of our goals, even if in retrospect, is to create better quantitative measures of placental function.

Finally, fetal oxygenation is a complex system involving fetal factors such as changing metabolic demand for oxygen, for example with growth or chorioamnionitis, changing anatomic resistance in the umbilical cord, such as occult prolapse, changing fetal hemoglobin levels with hemorrhage, and varying maternal factors such as intermittent hypoxia or hypotension. Dynamic systems often have non-intuitive outcome to changing variable values and parameters. Some of the changes can be small but can trigger lethal feedback if other parameters such a placental function were borderline. This ability of system analysis could clarify how stillbirths, perinatal asphyxia, and HIE are often unanticipated and without obvious anatomic cause. Systems analysis will be able to pinpoint the size of the risk and what might trigger a stillbirth for an individual patient.

The idea of creating a system model for a physiologic system is not novel. One paper in physiologic education found that it was a useful teaching technique even for students without advanced background in mathematics1. I am trying to find a group who agree that it is worth a try, given our apparent lack of success over recent decades in reducing the stillbirth rate.

To really make progress, the project needs knowledgeable and skilled modelers to interact with clinicians, (including pathologists) to start building a model. This is more likely to happen if we all have some basic understanding of the concepts and terms. Therefore, I want to share as a non-expert the basic concepts that I learned in the textbook, Modeling Life2, with others who may be contemplating joining in this Fetal Oxygenation (FOX) system project. To that end I am going to provide a section-by-section summary of the book, and from my perspective suggest how it might relate to pregnancy.

The excerpt below is from the introduction to the undergraduate textbook “Modeling Life The Mathematics of Biological Systems” by Alan Garfinkel, Jane Shevtsov and Yina Guo. They have used this course to teach physiologic modeling to premed students. You do not need to remember your calculus classes to understand the book, although they teach it in chapter 2 in a totally new way. I started from the beginning of the book and am now in the middle on the chapter on Nonequilibrium Dynamics: Oscillation and have not even gotten to the chapters on chaotic systems or on multivariable systems. I think the first chapter on Modeling, Change and Simulation may be enough to get an idea of what this type of modeling can contribute to understanding stillbirth. (note chapters are long in this book Chapter 1 is (1-68).

Excerpt from the Preface:

The book starts out with a familial ecological system, a very simplified version of predator and prey where the predator eats prey, which allows the predators to increase, but the prey decreases, then the predators don’t have enough prey to eat, which reduces the number of predators, allowing the prey numbers to increase, which then allows the predators to increase because there is more prey. The authors point out that this simplified system ignores many details, like weather fluctuations, disease breakout, plant abundance and many other things. This is a starter model, which is what we need to create for the relationship between fetal oxygen delivery and fetal oxygen consumption. The placenta sends oxygen to the fetus, the fetus consumes it, lowering the oxygen that returns to the placenta, the placenta then increases the oxygen, returning oxygen to the heart.

The goal is to translate systems like predator prey relationships, but also into many others, into a mathematical model. The book starts with a simple time series that can be obtained by observation of the number of prey and the number of predators over time. From the book.

To make this system reflect a fetal oxygenation system, we can relabel shark numbers to the fetal blood O2 level, and the tuna number to the cardiac output using “fetal heart rate” as a proxy (at least within narrow limits). Fetal O2utilization will decrease blood O2 which will by chemoreceptor/adrenergic reflex, increase cardiac heart rate, which will then increase O2 extraction from the placenta. That oxygen will be utilized by the fetus, thus returning to the beginning of the cycle.

The authors use this shark tuna example to show how this cycle relies on a positive and a negative feedback loop. A positive feedback loop increases a positive value and decreases a negative value (makes it more negative). A negative feedback loop decreases a positive value and increases a negative value (makes it less negative). Tuna to sharks is a positive loop: More tuna, more sharks which leads to a negative loop: More sharks, less tuna. They don’t make it explicit, but it takes two cycles to create the time series oscillation, as the then less tuna leads to less sharks as part of the return to the positive feedback loop, and in the second return to the negative feedback loop, less sharks leads to more tuna, and then the process repeats.

The text goes one step further with a section: Counterintuitive Behaviors of Feedback Systems. In real systems, there are multiple feedback loops such as the reproductive rate of the sharks and fish, etc. Removing most of the sharks in this system at a point in the cycle can unintuitively result in a stable increase in sharks.

The most obvious lesson here is that our model of fetal oxygenation needs to be a lot more complex to approximate reality and when we have it, there may be unexpected changes in response to a change in a system variable. Also, some system models will be better models of reality than others.

Section 1.2 Goes over basics of functions, maps the independent (input) value to the output (dependent) value, can be e.g. a table or a formula e.g. F(y) = 2x, or any other mapping as long as there is a single output value for each input value. X2 = Y2 is not a function since there are 2 values X = 2, and =-2. Not all functions can be written as a formula. For the shark tuna time series there is no formula for the graph. The important point for us is that for the overwhelming majority of biological models there is no known formula for the time series.

The input values that a function can accept is the domain. That domain is often all real numbers R, or all positive R+ numbers, with the restriction that the domain cannot result in division by a zero. In real world systems it is important to choose domains the make physical sense.

Section 1:3 States and State Spaces

The state of a system is the value of the state of quantitative variables at a given point in time. One of the hardest parts of building a model is deciding on the variables. Each state variable can have only one value at a given time, that is each is a function of time.

The state space is the set of all conceivable values of a system. Usually these are continuous variables, even if they don’t make sense, e.g. 3.1 rabbits. If they are not continuous, then a different kind of modeling is needed.

For a one variable system, the system state is a point on a line (its state space) at a given time. For example, fetal venous oxygen level would be a value on the line segment from 0 to the limits of the

Systems can have multiple values, and the values can be added if they are the same, apples to apples, and they can be multiplied by a scalar. They can also be graphed. For example, a two variable system can have its states plotted on an X, Y axis. For our system Maternal fetal (M, F )space would plot M, maternal PaO2 on one axis, and F, fetal Pa O2 on the other axis. Time is not plotted on the graph. But the point from one state to the next over time creates a vector The length of the vector is a scalar quantity, and the vector is the slope (in a single point a slope from 0,0 to M,F

To be continued.

References

1. Rubin DM, Letts RFR, Richards XL. Teaching physiology within a system dynamics framework. Adv Physiol Educ 2019;43(3):435-440. DOI: 10.1152/advan.00198.2018.

2. Garfinkel A SJ, Guo Y. Modeling Life The Mathematics of Biological Systems. Switzerland: Springer International Publlishing, 2017.

*************************************************************************************

Pathology cases

With any pathological exam of the placenta or autopsy, pathologists much like detectives, try to abduce a hypothesis about causation. Abduction, I learned on the internet, is what we do, as opposed to deduction or induction, that is we create hypotheses with incomplete information. The more clinical input, the more accurate those abductions are likely to be. The anatomic findings are real, and should not be ignored, but our best efforts as pathologists are not necessarily complete or correct. Progress in understanding will most likely occur if the clinician has a deep understanding of the pathology findings, and the pathologist has a deep understanding of the clinical case. To that end, these case reports are presented to prompt that understanding and discussion between pathologists and clinicians.

Case #1: A placenta with a long umbilical cord, marginal insertion, and chorionic surface thrombi.

The clinical history:

- Fetal growth restriction with the infant between 3rd and 10th percentile at birth at 38 weeks of gestation.

- Cesarean section because of suspicion of abruption and a biophysical profile of 4/8.

- Apgar scores were 8 & 9 at 1 & 5 minutes

Gross examination of the placenta

- 84 cm long umbilical cord with a furcate/marginal insertion.

- Birthweight to placental weight ratio, 6.8 (50th percentile)

- A remote marginal hematoma with little separation of the placenta

- An acute hematoma beneath the membranes

- Thickened grey chorionic veins on the surface of the placenta

Figure 1 This image shows the marginal cord insertion, long umbilical cord, and the large retro-membrane hematoma.

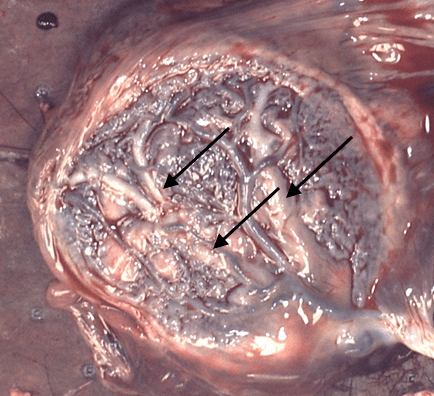

Figure 2 The arrows point to the thick gray veins that are identified as they run under the arteries. The cord insertion shows that the vessels leave the cord a little before the insertion making it uns

table.

Figure 3 The arrow points to one of the surface veins that has been cut and demonstrates a non-occlusive thrombus. The vein media is a ring of white tissue. There is a large thrombus forming an arc of yellow above the red blood.

Microscopic Findings:

- Remote, non-occluding mural thrombi in all large chorionic veins in the samples

- No distal fetal vascular malperfusion lesions

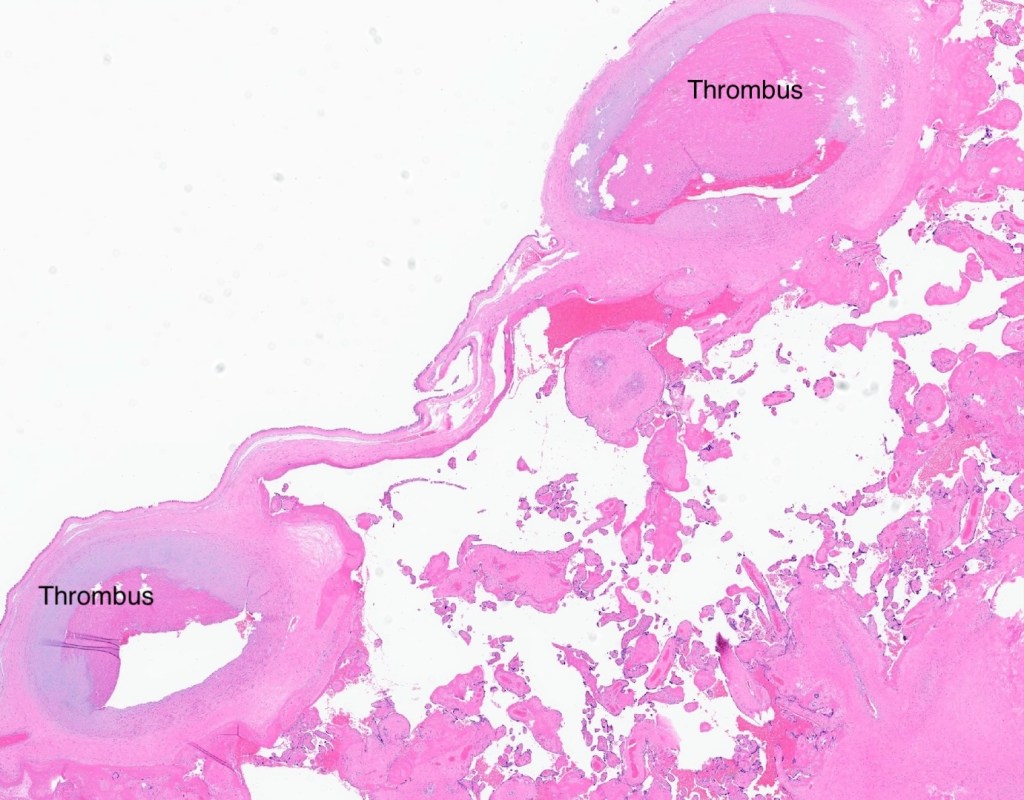

| Thrombus |

Figure 4 The microcopy confirmed the thrombi in all sampled chorionic surface veins. There were no distal lesions of fetal vascular malperfusion (H&E, 2x)

Figure 5 Shows the same features as Fig 4.

Abducing hypotheses from the case:

- Long umbilical cords are associated with fetal cord wrapping. This is discussed in the narrative view of long and short cords in this newsletter.

- Hypothesis 1: A wrapped umbilical cord can cause partial or complete collapse of the umbilical vein and decreased blood flow. This hypothesis is based on an vitro study3. A wrapped cord that starts near the placental insertion creates a short cord segment that is isolated between the beginning of the wrap and the placental insertion. In vitro, twisting this short segment will decrease umbilical venous flow (probably because the shorter the segment, the more the torsion on the umbilical vein per fetal rotation. Think of the effect of one twist on 4 cm of cord compared to 50 cm of cord).

- Hypothesis 2: Furcate insertions, which are often associated with marginal insertions, can not transfer a twist in the cord to the whole surface of the placenta, but rather will twist the exposed vessels. In furcate insertions, the vessels leave the protection of the umbilical cord before reaching the surface attachment.

- Hypothesis 3: A combination of cord wrapping, and unstable cord insertion led to partial occlusion of blood flow in the umbilical vein. This caused abnormal flow in the surface veins (think increased distal velocity, turbulence, and foci of stasis) that led to thrombi in the chorionic veins. The thrombi would eventually re-establish a smooth, but decreased, blood flow.

- Hypothesis 4: The decreased umbilical vein flow resulted in less placental perfusion and thereby decreased fetal growth, but ultimately the fetal and placental growth were balanced without fetal hypoxia. Of course, this infant could have been at risk of a sudden change with lethal hypoxia, but with Cesarean delivery, had normal Apgar scores.

Theoretical implications of these hypotheses:

- Umbilical cord length matters, but particularly the distance between a wrapped cord and the placental insertion. This might be detectable by ultrasound, and movement of the fetus might cause abnormal or decreased flow in the umbilical vein that might be detectable by Doppler ultrasound (usually done with the internal vein segment). This observation could be a measure of risk for fetal hypoxia or stillbirth. In this case, the known risk was an abnormal biophysical profile but the decision for a Cesarean section was based on a perhaps an incidental marginal hemorrhage, although a functional short cord and fetal descent may have caused the marginal separation.

- Abnormal changes in chorionic vein flows with fetal movement might also demonstrate a risk for fetal hypoxia and stillbirth.

- A balanced system of a small fetus, low umbilical venous blood flow, and a small placenta may appear stable, but may not be, for example if further compromise of fetal venous blood flow is induced by fetal movement such as descent into the pelvis.

Ref: Bendon RW, Brown SP, Ross MG. In vitro umbilical cord wrapping and torsion: possible cause of umbilical blood flow occlusion. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2014;27(14):1462-4. DOI: 10.3109/14767058.2013.866941.

A Review of long and short umbilical cords

The Clinical Significance of Short and Long Umbilical Cords

Précis:

Fetal cord wrapping creates, from the placental insertion to the beginning of the wrap, a functionally short umbilical cord with fetal hypoxia risk equivalent to a short cord.

Abstract:

Epidemiologic studies demonstrate associations of umbilical cord length with fetal gestation, size and sex. Abnormally short cords result from restricted fetal movement, demonstrating that fetal tension on the cord is a necessary stimulant for umbilical cord growth. The evidence is weak that abnormally long cords occur due to increased fetal motion. Long cords are associated with cord wrapping around fetal parts. This wrapping reduces the mobile length of the cord segment between the wrapping start and the placental insertion. Fetal movement would newly put tension on this segment of cord, reinitiating growth to reestablish the normal mobile cord length. How close the wrapping originally was to the placental insertion, and how much compensatory lengthening occurred, would determine the measured length of the whole cord after delivery. The wrapped cords would shift the distribution of cord length to a longer mean. Short and long cords demonstrate overlapping associations with proxy measures of fetal hypoxia. This overlap could be due to direct effects of a short cord whether a true short cord, or the short mobile segment created by wrapping if that segment did not achieve compensatory lengthening. A short length of the segment of umbilical cord between the placental insertion and the start of fetal wrapping may be an indicator of fetal risk for hypoxia. Suggestions for further research are presented.

The review:

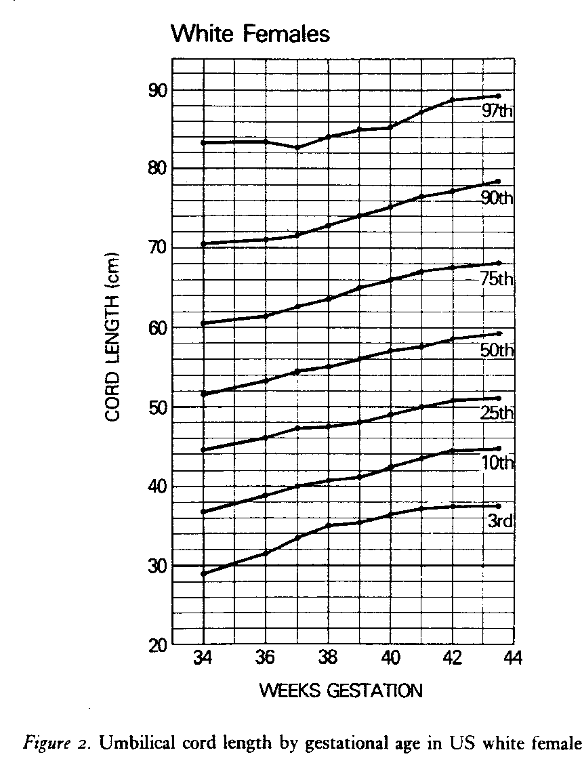

The normal distribution of the umbilical cord length varies by gestational age and size. Across international studies, the umbilical cords of term infants average 50-60 cm in length4-10. The umbilical cord grows throughout gestation, yet between 34 and 42 weeks of gestation the mean is usually within this 50-60 cm range (see below)4.

The mean length is longer the greater the birth weight and this relationship also holds for other variables directly related to birthweight such as maternal weight, maternal weight gain during pregnancy, placental weight, and male sex of the infant6. These relationships may not be true in all populations as a prospective study of 1,000 pregnancies from India did not find a significant association between cord length and birthweight or sex of the infant11. Published norms of umbilical cord length vary by whether they are based on clinical measures of the whole cord or on the cord received in pathology. The latter value can be reduced by segments of the cord removed for blood gases, banking of cord tissue, and length remaining attached to the infant. To complicate matters even more, the umbilical cord can shrink a mean of 3.5 cm, 23 hours after delivery12. Fortunately, as a practical matter, designating the length as pathologically short or long is based on the extremes of the distribution that are little effected by fetal weight and gestation, except for those under 34 weeks of gestation. Different studies have used different definitions. A short cord is usually diagnosed when the length is less than 35-40 cm, approximately below the 10th percentile or 1 standard deviation. An alternative definition of a short cord specific to labor could be defined for an individual patient based on an adequate length of cord to reach from the in situ placental insertion to the introitus, a length needed for vaginal delivery. A long cord, above the 90th percentile, is usually defined as >70 cm.

For a fetal gestation under 34 weeks, a separate gestational age distribution of cord length would be needed to determine cord length above or below a given standard deviation6. Midgestational stillbirths often have thin, long, and twisted umbilical cords13,14. The report of 3 recurrent stillbirths of one mother that had long, twisted cords and placental histology of fetal vascular malperfusion does not prove that this is necessarily a genetic syndrome13. An alternative explanation is that in mid-gestation the weight of the fetus suspended in sufficient amniotic fluid can passively stretch the cord leading to postmortem lengthening and thinning.

The dclinical significance of a short cord:

Short umbilical cords can result from both experimental and clinical fetal paralysis15-17. This observation led to the hypothesis that fetal movement puts tension on the cord that stimulates linear growth. It follows that a short cord could be a diagnostic indicator of neurologic, neuromuscular or muscle disease that decreases fetal movement or of conditions that restrict movement in utero. Smith and colleagues proposed the term fetal hypokinesia/akinesia sequence for the cluster of consequences of fetal paralysis which included short umbilical cord, pulmonary hypoplasia, and limb deformities, which are often severe and termed arthrogryposis congenita multiplex. Severe akinesia sequence can be lethal from pulmonary hypoplasia from respiratory paralysis. The experimental rat model used curare to paralyze the fetus. The same sequence of features in human infants was found with maternal treatment with curare for tetanus18, fetal spinal muscular dystrophy19, and anti-neuromuscular junction antibodies that crossed the placenta from mothers with myasthenia gravis20. The sequence designation also subsumed the older term Pena-Shokeir syndrome, which had the akinesia sequence features associated with brain abnormality21.

A short umbilical cord is also evidence of decreased intrauterine movement even if not so severe as to result in akinesia sequence. The experimental effect of a 35 % alcohol diet in maternal rats produces decreased fetal movement, and results in significantly shorter cords compared to controls22. One study using the cord lengths obtained in the Perinatal Collaborative Project found evidence that infants with trisomy 21, who typically are hypotonic in the nursery, had a significantly shorter average cord length, 45.1, compared to 57.3 for matched controls23. Shorter cords in rats were also found with maternal cocaine administration24. The diagnostic value of a short umbilical cord as a predictor of a prenatal origin of subsequent neurologic disease remains to be fully investigated.

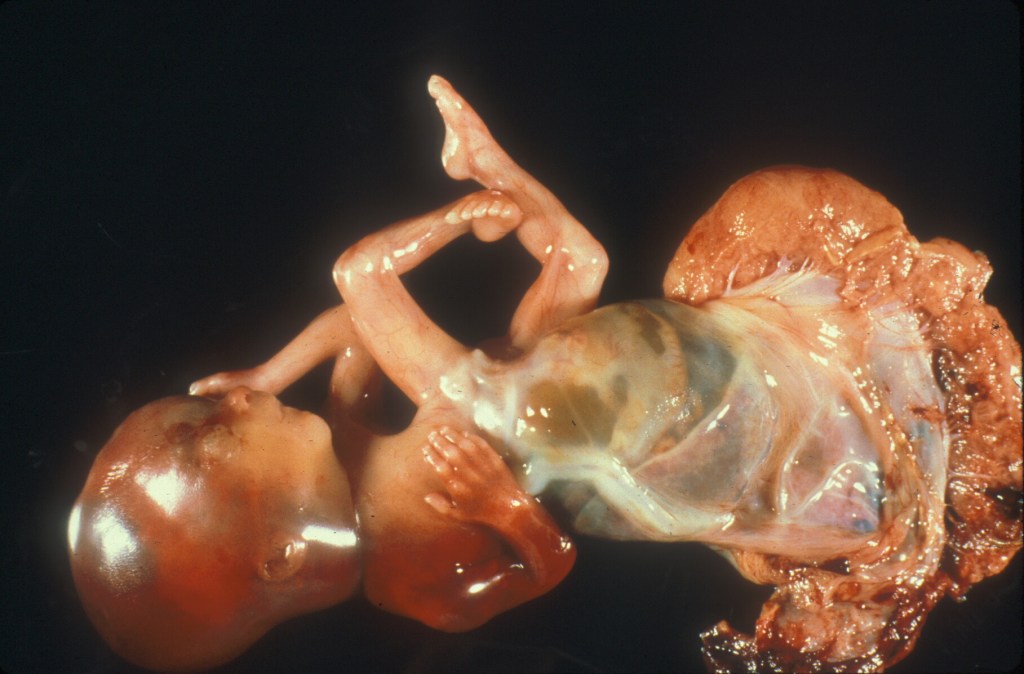

Physical restraint in a neurologically intact fetus can also cause hypokinesia/ akinesia sequence25. The most severe causes of short cord with intrauterine restraint are those associated with fetal adhesion to the placenta as in limb body wall defects and in early amnion rupture sequence (Fig 1) 26.

Figure 1 Limb body wall defect with a very short umbilical cord (arrow).

Some infants with severe oligohydramnios have a short cord from restricted movement. Not all cases of oligohydramnios are associated with a short cord. In one study 10 cases with renal agenesis, who therefore had no fetal urine and as a result had early onset anhydramnios, had cord lengths that were below 25 cm long from 20 to 38 weeks of gestation27. Some other causes of oligohydramnios in that study who had longer cords may have had later onset or incomplete loss of urine output.

Umbilical cords that are too short to allow normal descent of the fetus in labor while the placenta is attached to the uterine wall may demonstrate abnormal fetal heart tracing, require Cesarean section for arrest of fetal descent, or even cause a premature placental separation during delivery. A retrospective study of 80 cases of infants given in utero amnioinfusion for abnormal fetal heart rate tracings, predominantly persistent deep variables (a marker of cord compression), found that twelve infants still required a Cesarean section because of continued abnormal fetal heart rate28. This group had a statistically shorter umbilical cord. Seven of the Cesarean sectioned infants had nuchal cords. Wrapping an already short cord around the body creates an even shorter effective cord length. In a study of 5,885 deliveries, a cord less than 40 cm was associated with a greater incidence of operative delivery (forceps or Cesarean section)29. The authors’ discussion section noted that a loop of a short cord around the fetus would be more likely to be too short for delivery than with a longer cord. They suggested that a lack of correlation with compromised fetal outcome in some studies of cord length could be due to fetal monitoring leading to an operative delivery preventing complications from vaginal delivery. Many of the “short” cords in the above studies were not too short to allow delivery, so either they were further looped around the fetus shortening the free length, or they were compromising umbilical blood flow in another way. A short cord could theoretically decrease umbilical blood flow by being stretched during delivery thus increasing pressure on the vessels30, or being more susceptible to cord torsion from fetal rotation3.

The bottom line is that short cords may: 1) be a consequence of a fetal abnormality and those cases may hypokinesia or oligohydramnios sequence. 2) physically tether the fetus from traversing the path to a normal vaginal delivery, or 3) compromise umbilical blood flow. The latter two effects may be exacerbated by wrapping of the short cord around the fetus.

The clinical significance of a long cord:

If decreased fetal movement causes short cords, does fetal hyperactivity cause long cords? The evidence is not conclusive. In experimental studies in the rat, early gestational delivery into the abdominal cavity led to longer cords. The presumed explanation was increased fetal activity in the large abdominal space. A study of 62 women who had home devices that recorded fetal movement from maternal abdominal movement demonstrated that the only significant relationship of increased fetal movement with long cords (>60 cm) occurred only in the gestational interval from 36 to 39 weeks of gestation, and not at other gestations and cord lengths31. The authors had previously demonstrated that movement normally decreases in this late gestation time interval, but this occurs less in infants who develop long cords. The cause of hyperactivity in the infants was not investigated, nor the long-term outcome.

Another possible cause of long cords is the wrapping of the umbilical cord around fetal parts. After fetal cord wrapping only the cord segment between the placenta and the wrapped infant is free to move with the fetus. The wrapped cord is restricted by its entanglement. The length of this free segment will depend on how far the wrapping begins from the placental cord insertion. This free segment is the length of cord that will reach from the placenta to the introitus with descent of the infant, in addition to any length gained by tension on the wrapped cord with descent. If this length is too short to reach the introitus, it would compromise the infant’s delivery and overall reproductive success. However, fetal movement will put tension on the mobile segment causing it to lengthen by the same homeostatic mechanisms that occurred before it was wrapped. At delivery, the total cord length will now be this lengthened mobile cord segment plus the segment wrapped around the fetus. As a result, the delivered length is more likely to be > 70 cm. If the wrapping started close to the placenta, the mobile cord segment may still be short by the time of delivery, for example a wrapping starting 4 cm from the insertion might lengthen to 20 cm which would add to the 51 cm of the wrapped cord for a total of 71 cm. Actual cord wrapping may be more complicated as observed with the wrapping and unwrapping over gestation of nuchal cords32.

Figure 2 Multiple umbilical cord wrappings of a fetus delivered en caul showing the very short amount of free cord from the placental insertion to the fetal wrapping (double headed arrow).

Evidence in favor of this hypothesis is that long cords have been associated with cord abnormalities such as knots and nuchal cords that are evidence of cord wrapping. An example of the additive effect of a cord wrapping to a normal cord length is demonstrated by the progressive increase in cord length with an increasing number of nuchal cord loops, from 65 cm with one loop to 110 cm with 5 loops (see below)11.

# of loops # of cases mean umbilical cord length

| One loop | 124 | 65±15 |

| Two loops | 78 | 84±15 |

| Three loops | 15 | 95±15 |

| Four loops | 2 | 100±15 |

| Five loops | 1 | 110 |

An alternative hypothesis to explain the association of long cords with fetal wrapping is simply that a longer cord has a greater chance to become entangled around a fetal part. The longer length of the cord would be due to innate factors such as fetal size, genetics and perhaps (see above) hypermotility. If the later, there may be an underlying neurologic abnormality in some of the infants with a long cord.

A long umbilical cord has been associated with a long list of obstetrical complications. A comprehensive retrospective study of long cords (926 patients with cords ≥ 70 cm for gross pathologic and clinical review, and 129 for placental for microscopic review) found significant associations when compared to controls: including those expected to be found: placenta weight, and male sex14; those attributable to fetal hypoxia: asphyxia at birth, low Apgar scores, delivery complications, meconium macrophages in the fetal membranes, and non-reassuring fetal status; those associated with cord wrapping: cord knots, cord twisting, and abnormal presentation; those with microscopic features consistent with compromised fetal blood flow: fetal vascular thrombi, intimal cushions and chorangiosis (excessive villous capillary proliferation); and those with more complex outcomes without simple interpretations: maternal disease, fetal anomalies, and increased syncytial knots (a likely response to maternal under perfusion of the placenta). Long cords more generally have been associated with histological placental features of fetal vascular malperfusion33. Other studies have associated long cords with stillbirth or neurologic injury although studies are sometimes contradictory. A recent meta-analysis of umbilical cord lesions associated with stillbirth rejected including the analysis of cord length because of the lack of uniformity in the diagnosis of abnormal length34.

Unlike the tethering effect of short cords, there is a lack of evidence of direct harm from long cords. There are some older papers that identified long cords as increasing the risk of umbilical cord prolapse, but recent papers have concentrated on stronger risk factors for prolapse such as polyhydramnios (more room to move) and non-vertex fetal presentation (possible complex cord entanglement) which might be associated with longer cords35.

A longer cord might increase fetal vascular resistance. With Newtonian flow in a tube, resistance is directly related to length. A modest increase in vascular diameter, a third power relationship, would compensate for the increase in length. Long helical vessels may theoretically increase mural shear stress, but such an effect would not explain the increased risk of hypoxia with longer cords, as most long cords to not have compromised infant outcomes.

Early modern obstetrical studies of cord length noted that that the complications associated with both short and long cords were similar. “Inadequate fetal descent was significantly more common when a long cord or an excessively short cord (25 cm of less, lower first percentile), was found. Fetal heart rate (FHR) abnormalities that primarily reflected cord compression were significantly more frequent in the presence of a short (17 of 27 cases, 63%) or al long cord (28 of 32 cases, 87%) as compared with a normal length cord (145 of 393 cases 37%)” 5. A subsequent study demonstrated that arterial blood cases were not abnormal in most infants with a long or short umbilical cord36. However, if the fetus also had severe deep variable heart rate decelerations or bradycardia, then an umbilical blood pH below 7.2 was found with 2 of 61 short cords and 5 of 111 long cords.

If long cords are initiated by fetal wrapping, a reasonable hypothesis is that if the segment of cord between the beginning of the wrapping and the placenta has not had time to grow longer to compensate, then the that free length of cord from the placenta may still be too short, and hence subject to the same complications as a short umbilical cord. This is more likely if the initial distance from the wrap to the placenta was very short. Some complications, such as vascular occlusion from fetal rotation that twists a very short cord, could occur prior to labor3.

Practical considerations

The pathology report can only record the length of the cord received. Ideally, the clinical history should record the full length. A true short cord may have explanatory value, for example of the need for an operative delivery. In medical legal cases, the short cord may be useful evidence supporting an early origin of a neurological injury. A standard protocol for the medical institution for measuring and recording fetal cord length would make the length more useful in clinical studies.

There is no receiver operator optimum cut off determined for short or long cords. As a rough screening tool, current criteria are less than 35 cm for a short cord, and more than 70cm for a long cord. Diagnostic end points for short or long cords based on percentiles or standard deviations might need to be adjusted for gestational age, birthweight, and fetal sex. The short cord length to account for the arrest of labor may depend on the distance the fetus must traverse to the introitus from the placental insertion. The relationship of short cord length to fetal hypokinesia may depend on the severity and duration of decreased fetal movement. Adverse outcomes associated with long cords may depend more on the free segment of the cord between the onset of wrapping and the placental insertion than on the delivered length of the cord.

Research potential related to umbilical cord length:

Basic Science: The umbilical cord has a simple structure. It is without a capillary bed, has a helical collagenous structure firmly attached to the vessels and surface, and has a colloid glycosaminoglycan matrix full of fibroblasts, primitive stem cells and some mast cells. Longitudinal tugging on the cord appears to initiate growth. Such growth needs to be modulated between two evolutionary goals for reproductive survival, primarily having a cord long enough to safely deliver a viable infant even if wrapped around its body parts, and secondarily not to overshoot the length potentially wasting nutrients, and potentially increasing fetal entanglement, and vascular resistance. How this feat is accomplished seems ripe for some basic discoveries. How does the coiled structure of the cord respond to longitudinal tension and the release of active growth factors? How is this stimulus damped down if the tension is transient?

A study using immunohistochemistry for “growth and apoptotic” factors on 31 umbilical cords from stillborn infants who had a wide array of other findings and cord lengths found differences in expression, but little clarity37. Definitive experiments could be conducted on segments of human umbilical cord that are viable and perfused with needed oxygen and nutrients. Then the molecular effects of stretching, twisting, hypoxia and blood pressure could be investigated directly.

Clinical Science: With the advent of 3D ultrasound and with MRI techniques, the cord length can be surveyed and measured during the pregnancy to study changes in length and the relationship to wrapping, and other complications such as prolapse or possibly premature placental separation38,39. The cord length could be directly related to fetal movement, to placental insertion site in the uterus, and to Doppler hemodynamics. Measurement of the length of the segment from the placental cord insertion to the start of the fetal wrapping could evaluate the rate of growth as well as the use of this segment of cord to predict fetal hypoxic complications. An in vitro study demonstrated that a rotation of a short segment of cord creates a greater change in vascular pitch (coiling index) than in a longer cord, and more severe compromise of umbilical vein blood flow, but in vivo studies are lacking3. The acute effects of tension with descent on a short cord or short mobile segment of cord are incompletely understood. Prepartum studies of the actual and the free cord length may predict risk of stillbirth, perinatal asphyxia, or delivery complications. A functional short cord segment from cord wrapping may be an intrapartum detectable cause of recurrent deep variable fetal heart tone decelerations during labor.

References:

1. Mills JL, Harley EE, Moessinger AC. Standards for measuring umbilical cord length. Placenta 1983;4(4):423-6. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=6634668 ).

2. Rayburn WF, Beynen A, Brinkman DL. Umbilical cord length and intrapartum complications. Obstet Gynecol 1981;57(4):450-2. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=7243092 ).

3. Naeye R. Umbilical cord length: clinical significance. J Pediatr 1985;107:278-281.

4. Sarwono E, Disse WS, Oudesluys Murphy HM, Oosting H, De Groot CJ. Umbilical cord length and intra uterine wellbeing. Paediatr Indones 1991;31(5-6):136-40. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=1896194 ).

5. Malpas P. Length of the Human Umbilical Cord at Term. Br Med J 1964;1(5384):673-4. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=14096463 ).

6. Adinma JI. The umbilical cord: a study of 1,000 consecutive deliveries. Int J Fertil Menopausal Stud 1993;38(3):175-9. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=8348167 ).

7. Agboola A. Correlates of human umbilical cord length. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1978;16(3):238-9. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=33085).

8. Shiva Kumar HC, Chandrashekhar T. Tharihalli, Chandrashekhar K., Suman F. Gaddi. Study of length of umbilical cord and fetal outcome: a study of 1000 deliveries. International Journal of Reproduction, Contraception, Obstetrics and Gynecology 2017;6(9):3770-3775.

9. Manci EA, Alvarez SS, McClellan SB, et al. Biphasic Postnatal Umbilical Cord Shortening. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2021;24(2):116-120. DOI: 10.1177/1093526620984258.

10. Slack JC, Boyd TK. Fetal Vascular Malperfusion Due To Long and Hypercoiled Umbilical Cords Resulting in Recurrent Second Trimester Pregnancy Loss: A Case Series and Literature Review. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2021;24(1):12-18. DOI: 10.1177/1093526620962061.

11. Baergen RN, Malicki D, Behling C, Benirschke K. Morbidity, mortality, and placental pathology in excessively long umbilical cords: retrospective study. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2001;4(2):144-53.

12. Miller ME, Jones MC, Smith DW. Tension: the basis of umbilical cord growth. J Pediatr 1982;101(5):844. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=7131174 ).

13. Moessinger AC, Blanc WA, Marone PA, Polsen DC. Umbilical cord length as an index of fetal activity: experimental study and clinical implications. Pediatr Res 1982;16(2):109-12. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=7036074 ).

14. Moessinger A. Fetal akinesia deformation sequence: an animal model. Pediatrics 1983;72:857-63.

15. Jago RH. Arthrogryposis following treatment of maternal tetanus with muscle relaxants. Arch Dis Child 1970;45(240):277-9. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/5420008).

16. Kizilates SU, Talim B, Sel K, Kose G, Caglar M. Severe lethal spinal muscular atrophy variant with arthrogryposis. Pediatr Neurol 2005;32(3):201-4. DOI: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2004.10.003.

17. Smit LM, Barth PG. Arthrogryposis multiplex congenita due to congenital myasthenia. Dev Med Child Neurol 1980;22(3):371-4. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6446471).

18. Lavi E, Montone K, Rorke L, Kliman H. Fetal Akinesia Deformation Sequence (Pena-Shokeir Phenotype) Associated with Acquired Intrauterine Brain Damage. Neurology 1991;41:1467-1468.

19. Barron S, Riley EP, Smotherman WP. The effect of prenatal alcohol exposure on umbilical cord length in fetal rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1986;10(5):493-5. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=3541671 ).

20. Moessinger AC, Mills JL, Harley EE, Ramakrishnan R, Berendes HW, Blanc WA. Umbilical cord length in Down’s syndrome. Am J Dis Child 1986;140(12):1276-7. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=2946222 ).

21. Barron S, Foss JA, Riley EP. The effect of prenatal cocaine exposure on umbilical cord length in fetal rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol 1991;13(5):503-6. DOI: 10.1016/0892-0362(91)90057-4.

22. Miller M, Higginbottom M, Smith D. Short umbilical cord: Its origin and relevance. Pediatr 1981;67:618-21.

23. Kalousek DK, Bamforth S. Amnion rupture sequence in previable fetuses. Am J Med Genet 1988;31(1):63-73. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=3223500 ).

24. Izumi K, Jones KL, Kosaki K, Benirschke K. Umbilical cord length in urinary tract abnormalities associated with oligohydramnios: evidence regarding developmental pathogenesis. Fetal Pediatr Pathol 2006;25(5):233-40. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17438663 ).

25. Iwagaki S, Takahashi Y, Chiaki R, et al. Umbilical cord length affects the efficacy of amnioinfusion for repetitive variable deceleration during labor. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2022;35(1):86-90. DOI: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1712703.

26. Sornes T. Short umbilical cord as a cause of fetal distress. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1989;68(7):609-11. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=2631528 ).

27. Pennati G. Biomechanical properties of the human umbilical cord. Biorheology 2001;38(5-6):355-66. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12016319).

28. Bendon RW, Brown SP, Ross MG. In vitro umbilical cord wrapping and torsion: possible cause of umbilical blood flow occlusion. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2014;27(14):1462-4. DOI: 10.3109/14767058.2013.866941.

29. Ryo E, Kamata H, Seto M, Morita M, Yatsuki K. Correlation between umbilical cord length and gross fetal movement as counted by a fetal movement acceleration measurement recorder. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X 2019;1:100003. DOI: 10.1016/j.eurox.2019.100003.

30. Collins JH, Collins CL, Weckwerth SR, De Angelis L. Nuchal cords: timing of prenatal diagnosis and duration. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995;173(3 Pt 1):768. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=7573240 ).

31. Ma LX, Levitan D, Baergen RN. Weights of Fetal Membranes and Umbilical Cords: Correlation With Placental Pathology. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2020;23(4):249-252. DOI: 10.1177/1093526619889460.

32. Hayes DJL, Warland J, Parast MM, et al. Umbilical cord characteristics and their association with adverse pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2020;15(9):e0239630. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239630.

33. Lin MG. Umbilical cord prolapse. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2006;61(4):269-77. DOI: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000208802.20908.c6.

34. Berg TG, Rayburn WF. Umbilical cord length and acid-base balance at delivery. J Reprod Med 1995;40(1):9-12. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=7722985 ).

35. Olaya CM, Fritsch M, Bernal JE. Immunohistochemical protein expression profiling of growth- and apoptotic-related factors in relation to umbilical cord length. Early Hum Dev 2015;91(5):291-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2015.03.001.

36. Collins JH. The Case for Umbilical Cord Screening Via Ultrasound at 18–20 Weeks. Med Res Arch 2021;9(10):1-10.

37. Katsura D, Takahashi Y, Shimizu T, et al. Prenatal measurement of umbilical cord length using magnetic resonance imaging. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2018;231:142-146. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.10.037.Letters on Obstetrical Pathology LOOP Volume 1, number 1