The basis of the coil (helix) in the umbilical cord

The coiling index (CI) is defined as the number of complete externally visible twists per 10 cm of cord1 (A review of the history and medical literature related to coiling index prior to 2005 is available2.) Because the umbilical vessels are attached to the “skin” of the cord, the external twists follow the helix of the umbilical vessels (Fig 1). Antenatal sonography has identified differing relationships of these vessels in the helix: 1) no coiling of vessels (zero coiling index), 2) a straight or gently undulating umbilical vein with arteries coiling around it, and 3) a mutual coiling of the vein and arteries as a combined helix3. Ultrasonographers, because of difficulty finding a long straight segment in utero, may obtain the coiling index by measuring the reciprocal which is the length of a single complete helix. For example, if a single helix measures 5 cm, then the inverse is the coiling index of 2 per 10 cm. There is some evidence that the number of coils is not uniform over the whole cord with more toward the fetal end of the cord4. The entire length of the umbilical cord is seldom available, and an index from a single segment may therefore not be identical to the value for the whole cord. The coiling index does not inform us about the total number of coils or the length of the cord, but only the ratio of those two values determined over a given segment.

Figure 1 This segment of an umbilical cord in which the umbilical vein was perfused with green dye demonstrates that the vascular helix is follows the external helix of the cord.

Coiling of the umbilical vessels starts early in gestation and has been reported to be complete by 9 weeks of gestation with a range of the uniform right handed twists from 1 to 29 (mean 7.5) and that of the lefthanded twists from 1 to 19 (mean 6.7)5. If the vessels are not restrained in the Wharton’s jelly, then the formation of a vascular helix is determined by physical forces. A vessel with kinetic energy from the blood flow is going to strike the cylindrical outer wall of the cord if the path of the cord curves relative to the vessel. This can be demonstrated very simply with some rubber hoses (Fig 2). The video demonstrates that the angle of initial flow determines the handedness of the helix and that as pressure is increased as the flow is released, the number of coils increases from one to two. Presumably if there were two arteries linked, the handedness of the coils might eventually be dominated by the artery with the higher flow/pressure. This neat prediction, however, does not explain cords that change handedness mid cord. While fewer coils occur with lower pressures, in the cord the number of coils could also be decreased by the dampening effect of the viscosity of the Wharton’s jelly. The model in the video below could not empirically test the effect of viscosity as the large tube was filled with air. As the length of the cord increases during gestation, the vascular helix requires that the vessels grow faster than the linear growth of the whole umbilical cord because their curved path is longer. An increase in vascular helices could be created if the growth of the vessels sufficiently exceeded that of the cord length. The bottom line is that knowledge of the underlying processes that determine the coiling index is still incomplete.

As gestation progresses, the vessels become bound to the cord surface by the collagen network in Wharton’s jelly. The strength of this attachment is evident if one tries to dissect a vessel at term from the interior of the umbilical cord. If the helix was fully formed at 9 weeks with an average of 7 coils in an average 50 cm cord, the coiling index would be 1.4 coils per 10 cm. This is within in the range of normal clinical values. If the number of coils remains constant as the cord grows, the coiling index would decrease with linear cord growth. Therefore, any association of coiling index with clinical associations would also be dependent on cord length.

There is currently no definitive proof that coils can increase or decrease over gestation. A careful study of 159 postpartum umbilical cords reported that there was no association of coiling index with gestation or birthweight4. However, this study was very concentrated on AGA term infants (39.1 +/- 1.2 weeks of gestation, 3,199 +/- 40 g birthweights) and would not reflect the period of fastest cord growth. Conceivably, the coil number could change because of changes in fetal blood pressure, fetal twisting in utero, or changes in intrinsic regulation of vascular growth as the cord lengthens. Attempts to clarify when and if the number of coils change during gestation have been made with serial ultrasound examinations during pregnancy. Unfortunately, direct longitudinal observation of changes in cord coiling index by ultrasound has been hampered by the difficulty in viewing the entire length of the cord at one session6. The correlation of ultrasound determined coiling index compared to postpartum coiling index has varied. In a recent study, there was a strong correlation, but interestingly the published plot showed many outliers7. Those cases would be interesting to study in more detail. The study also did not publish the techniques used to obtain the measurements.

Twin to twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS)

Several studies have noted discordance in the coiling index of monochorionic twins8,9. This is evidence against a direct inheritance of the number of coils. In TTTS there is discordance not only of body size and blood flow to the kidney (amniotic fluid production), but also of heart size and hence cardiac volume pumped with each contraction. The evidence points to hypertension in the recipient and hypotension in the donor. TTTS is not a steady state transfusion, but an unbalanced equilibrium between twins sharing a placental circulation. Hypothetically, this twin-to-twin equilibrium would be established during the connection of the umbilical cord to the placental vasculature in the first trimester at a time when the initial helix is being stabilized in the umbilical cord. The data from a study of the coiling index in twin pairs with TTTS supports this hypothesis9. A coiling index was obtained by ultrasound of a single helix, in 65 TTTS pairs that were referred for evaluation of laser division of the chorionic circulations. In 56 pairs the coiling index was recorded in both twins. The mean coiling index of the recipients was significantly higher than that of the donors. As the study was done at a referral center there was no follow up of the postpartum coiling index (nor of cord length and total coil number which may be independent of each other). The usual Doppler indices did not show significant differences between twins. The vessel diameters were not measured, but a reasonable assumption is that the donor’s arteries were smaller in diameter and had a smaller volume flow. The most interesting result was presented in a scatter plot of the index for each pair of twins. The majority showed a steep downward slope, but 8 showed a steep upward slope. Unless these were data entry errors, this anomaly needs a physiologic explanation. While it may be coincidence, 8 pairs were at Quintero stage 1. As with many studies evaluating association of different outcomes, inferences about possible mechanisms would benefit if the data was analyzed with more data points for each individual with associations calculated in N-space. Even more simply, the presentation of the data could show multiple dimensions, for example line color could have displayed the Quintero stage of the pairs in coiling index scatter plot.

In utero twisting of the cord:

Extraneous twisting of the cord during the fetal rotation through the pelvis or fetal twisting in utero (or as was once popular among obstetrical residents, twisting the umbilical cord to hopefully accelerate the third stage of labor (delivery of the placenta)) could increase the perceived coiling index. An externally induced coil would occur if the fetus were to rotate axially in one direction in utero. This could even occur passively in a generous volume of amniotic fluid as the random vectors of maternal motion summed into a rotary force along the walls of the uterus (Fig 3).

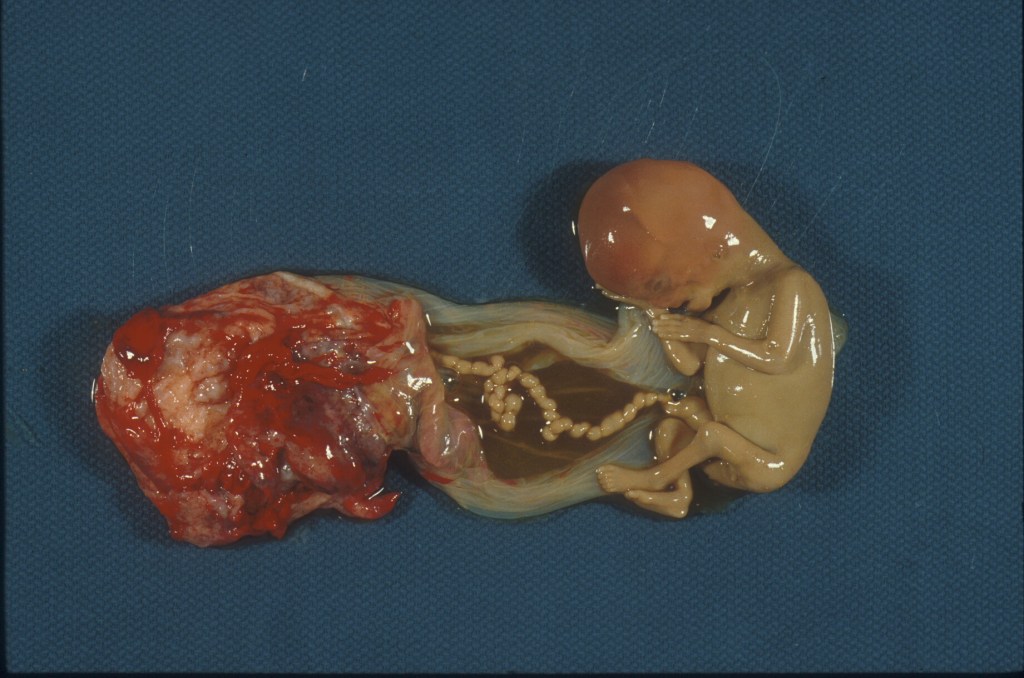

This passive postmortem twisting could be an explanation for the long, twisted cords common in mid-trimester stillbirth. Without direct observation, separating cause (abnormal cord caused the death) from effect (death allowed the long, twisted cord to develop) is difficult. An argument for the latter is that some mid-gestation stillbirths with a cause of death unrelated to the cord, still show a long, thin, hyper-twisted umbilical cord (Fig 4). This twist is often most constricting at the umbilicus. A compromised fetus might be less able to resist the passive rotary motion in utero and be more subject to lethal passive twisting. Direct observation in utero could resolve how these twisted cords are related to fetal death.

Figure 3 The umbilical cord is tightly coiled as seen in this photo near the umbilicus. This fetus died of a 50% retroplacental hematoma (placental abruption) with progressive heart failure from hypoxia. The histology of the twisted cord did not show acute inflammation or fibrin deposition.

The handedness of the cord coiling.

Handedness of a coil or helix is demonstrated by pointing along the cord with the thumb and then looking at the direction of the coil matches the fingers of the left or right hand. In an early, but detailed discussion of umbilical cord handedness there was a 75% predominance of left-handed cords which has been confirmed in multiple studies10. This paper also demonstrated that single umbilical arteries were associated with right-handed or absent coiling and that the direction of the helix did not correlate with the dominate hand of the children. The video in figure 2 demonstrates how the angle of incidence of the dominant umbilical arterial flow entering the cord might determine the handedness of the umbilical vascular helix. There is no intrinsic reason that right or left handedness would affect the resistance to blood flow. One study found significant associations of fetal death and histologic evidence of fetal vascular malperfusion with right handed coils suggesting that congenital differences in relative right and umbilical artery blood flow might have some lasting effect11.

The morphology of coils on the surface of the cord.

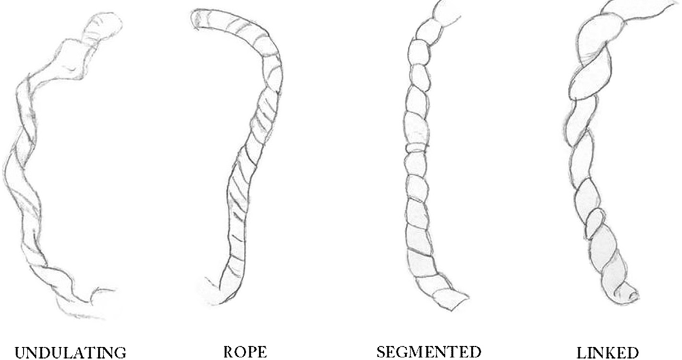

A study tested the observation that different morphology of the umbilical cord would have different clinical associations11. The study proposed 4 classifications of the types of coiling, which were later in the analysis divided into just two categories. The illustration from the paper is reproduced below.

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of the four gross umbilical cord coiling patterns.

In the dichotomous analysis, the left 2 forms were combined as having smooth coiling, and the right two forms were combined for having deep constricting grooves in the cord. The deep grove combination was associated with fetal vascular malperfusion lesions in the placenta and with fetal death. Even when the stillborn cases were removed, the association with the deep groove cord patterns remained. The coiling index did not correlate with outcome. However, right-handed twists correlated with the deep groove patterns and hence with the fetal vascular lesions.

The discernment of significance to the deep grooved pattern of coiling is a novel observation. The deep grooves appear to have collapsed the underlying umbilical vessels. Since some of the infants with this pattern were live born, this could not be true. One explanation is that the postpartum state of the cord is not equivalent to the living state, as can easily be demonstrated in ultrasound cross sections of the cord in living fetuses. The grooves might be areas where the Wharton’s jelly was squeezed thin. Torsional stress against the cord (that is an outside torsional stress, not the effect of the vascular helix), could have caused the thinning. After collapse of the vascular volume with deliver, the thinned areas would collapse. The associated microscopic lesions of fetal vascular malperfusion are usually attributed to decreased umbilical blood flow, or in rare cases to fetal thrombophilia12. These lesions appear distal to thrombosed placental vessels, but also occur without observable thrombi. Some of these lesions takes days to develop based on the Genest timing of the postmortem development of similar lesions13. Hypothetically, fetal hypoxia could make the fetus less able to resist the passive torsion of maternal movement, and therefore more likely to suffer decreased blood flow from cord torsion. Thus, even in living infants, the grooves could be a secondary to hypoxia not a cause. The correlation of the grooves with handedness requires an explanation and studies in living fetuses may be able to find abnormal blood flow in some right-handed cords.

Figure 4 A first trimester fetal loss still attached to the placenta with the long, hypercoiled, deep groove patterned umbilical cord

Figure 5 An anemic umbilical cord with deep grooves from a 19 week gestation stillbirth.

The correlation of the deep groove pattern with stillbirth could be a continuation of whatever mechanism was causing the grooves and placental lesions. However, as seen in long thin cords, the grooves in the stillborn infants could be postmortem effects from rotation.( Fig) Stillborn infants in the third trimester also sometimes have unexplained umbilical cord edema and angulated grooves and twists. Possibly changes in Wharton jelly metabolism following fetal death cause osmotic edema from amniotic fluid and the loss of the integrity of the fibrous network structure, already weakened by the loss of fetal blood pressure in the vessels. Knowing which changes are premortem and which are postmortem is important in the effort to deduce the cause of death.

Deep grooves can be reproduced by twisting the umbilical cord after delivery. The cord below shoes the effect of twisting the cord which have the vein partially filled with red dyed radiologic barium contrast solution.

Figure 6 This is before one end was twisted

Figure 7 This is after the twist was applied showing formation of deep grooves.

Biological cost and benefits of the cord helix

The often-suggested benefit of the vascular coiling of the umbilical cord is to prevent compression of the umbilical vessels from twisting, kinking, and direct compression. Mechanical umbilical cords for undersea and outer space respiration use a coiled design to protect flow. For example, this statement was in an advertisement for Divex diver’s umbilicals “twisted umbilicals offer significant advantages including great flexibility and strength while resisting kinking, and abrasion due to the inherently strong ‘rope like’ structure”. In the umbilical cord it makes sense that pulling on the cord could narrow and stretch the cord, but that the vessels would only uncoil and be less compressed than the cord itself. If Wharton’s jelly flows with applied stress, then the movement of jelly away from a locally stretched segment of the cord may further reduce compression on the umbilical vessels.

A study compared segments of umbilical cord with hypocoiling (≤1 Coiling Index, N=4)) to normal coiled cords (Coiling Index 1-3, N=6) using 1) clamping to measure the decrease in cord width, and 2) twisting and stretching to measure the decrease in umbilical vein in vitro flow14. There was no significant difference between the differently coiled cords, although increasing the torsion and stretch did reduce the flow. They did not take the experiment to the collapse of the vein.

Another in vitro modeled the tightening of a wrapped cord by applying increasing weight to a standard cord wrapping around a pipe and measuring venous flow of Ringer’s lactate at 40 mm HG pressure to the point of flow cessation15. They found, counterintuitively, an inverse relationship between coiling index and the weight needed to stop flow. More coiling reduced the protection of the cord to increased stretching force. Their data also showed the coiling index was significantly higher in the growth restricted infants who also had significantly lower mass index (cord weight/ cord length). Thus, their results on coiling index may have been biased by the inclusion of the growth restricted infants. Their lighter cords could have less collagen strength, or intrinsically increased impedance to flow in a narrow, hypercoiled cord that overrode any protective effect of the coiling. The multivariate analysis of the data did show the coiling index to be an independent factor. Infants of diabetic mothers required more weight to stop flow, independent of their birthweight for gestation status (LGA or AGA).

The bottom line is that the benefit or lack of benefit of the vascular helix in protecting umbilical blood flow has not been proven.

The cost of the coiling is the increased length of the vessels (compared to the cord length) and the increase in wall shear stress which would both impede flow requiring higher fetal blood pressure for the same volume flow of placental perfusion. In an attempt to better understand the effect of physical parameters, such as the number of coils, the pitch of the coils, and the diameter of the helix (essentially the diameter of the umbilical cord), a geometric model was constructed with 3D CAD software (Solidworks) relating the artery diameter directly with a constant parameter to the coil diameter and the pitch directly to the coil diameter modified by another parameter16. A commercial software package (ANSYS) ran several modifications of the parameters and solved for basic hydrodynamic equations based on the Navier-Stokes equation and using published norms for blood density and dynamic viscosity. The effects of the parameter changes on flow, pressure and wall shear stress were compared to those in a straight tube. The total number of coils had little effect on the shear stress but decreasing the pitch (fewer coils per length of cord) lowered the shear stress. The highest stress increase was in the model with a narrow coil (cord) diameter and very high pitch. The study also used a model with pulsatile flow and found that the pressure effects averaged to the steady flow model. The modeled pressure and flow values were within the range of measured fetal cardiac output.

Another published study of flow in umbilical coils used a different approach by calculating pressure drops predicted by various continuous hemodynamic functions using values determined empirically or theoretically17. They applied their model to measurements on a real hypercoiled, knotted umbilical cord to evaluate the effect of the untightened knot on the predicted pressure drop. Their results are similar to the physical model study: ”A ratio of the pressure drop over the coiled length to the pressure drop over its straightened length, which we term the coil pressure anomaly (𝛥𝑃̂∕𝛥𝑃̂ ), is shown in b). This reveals a competing trend; tightly wound cords with high UCI and low width have a pressure drop most affected by the coiling, though even the normally coiled reference vein has a coil pressure 50% higher than if it was straightened.” The bottom line is that narrow, very coiled cords take more energy to perfuse than less coiled, wider cords, and those cords require more energy than similar dimensioned straight cords. In effect, the coils create impedance that requires an increase in pressure to maintain a given flow of blood. This is not an unexpected result.

These rigid models do not account for the ability of smooth muscle to expand with perpendicular wall pressure and then contract using metabolic energy. As pathologists without an engineering background, it is difficult to understand how closely the models compare to the in vivo umbilical cord blood flow. The models do not address the dynamics that determine the form the coil in an embryo and how the fetal cord adaptations to maintain a vital blood flow homeostasis. The models do not answer directly whether the coils are an intrinsic unavoidable process or whether they are conserved and modified because they provide a reproductive benefit in protecting the cord.

Practical determination of the coiling index

Before considering clinical associations with CI, the importance of significant variability in how the coiling index is determined needs to be considered. This paragraph is indebted to a detailed consideration of this problem by Dr. Yee Khong6. There are significant difficulties of obtaining an accurate coiling index that can result in misclassification of cords as hypo or hypercoiled. Because of an uneven distribution of coils over the length of the cord, the coiling index depends on whether a whole cord or a segment is measured. Postpartum shrinkage of the cord and applied stretching of the cord to straighten it for measurement may affect the length used to obtain the coiling index without changing the number of coils. The coiling index will also vary depending how partial helices and helices that change direction over the length of the cord are counted. How pseudoknots are counted is yet another variable. Attention to the details of how the count is obtained, at least for research, is critical to obtaining valid and reproducible results. Currently the importance of precision in the coiling index with clinical associations has not been investigated.

Clinical associations of coiling index:

There have been many papers associating low and high coiling index, usually as the lower and upper tenth percentiles, with clinical outcomes. A meta-analysis published in 2020 summarizes those associations that survived rigorous statistical techniques as quoted below from the abstract.

“Twenty four studies were finally included that involved 9553 pregnant women.

Umbilical cord coiling was evaluated with the use of the umbilical coiling index (UCI). Values of the UCI below the 10th percentile were evaluated as hypocoiled and above the 90th percentile ss hypercoiled. Hypocoiled cords were significantly associated with increased prevalence of preterm birth<37 weeks, need for interventional delivery due to fetal distress, meconium-stained liquor, Apgar scores<7 at 5 min, small for gestational age (SGA) neonates, fetal anomalies, need for admission in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), fetal heart rate abnormalities, and fetal death.

Hypercoiled cords were significantly associated with increased prevalence of preterm birth<37 weeks, need for interventional delivery due to fetal distress, meconium-stained liquor, Apgar scores<7 at 5 min, small for gestational age (SGA) neonates, fetal anomalies, fetal growth restriction, fetal heart rate abnormalities, fetal acidosis, and fetal death.”

The most striking observation is the overlap of clinical associations between infants with either low or high coiling index. Secondly, many of the associations are reasonably considered non-independent measures of fetal hypoxia during labor. An analogous pattern of increased risk of fetal hypoxia with either short or long umbilical cords suggests that the associations of length and coiling index could be related. If we accept that the number of coils is determined early in gestation, and that continued linear growth of the cord decreases the coiling index, a reasonable hypothesis is that the associations could be due to the length of the cord, which has proposed mechanisms for fetal hypoxia for both long and short cords. There are proposed mechanisms in which coils impede umbilical blood or protect it, but they have so far not proven to be of large magnitude (see above on benefits and cots of coiling). The metanalysis did not include cord length as a variable.

The association of hypercoiled cords with both preterm gestation and growth restriction can be explained by the same hypothesis in that both increasing birthweight, and at least early third trimester gestation are correlated with increasing cord length. Low birth weight and gestation therefore should have shorter cords and higher coiling index. This does not explain the association of preterm birth with hypocoiled cords. Some cords have no or very few coils, and these fetuses may have an intrinsic low cord blood flow that led to early obstetrical intervention and biased the results. Preterm delivery is not equivalent to preterm labor. The data to prove or contradict such speculation is not available. The association with fetal anomalies and fetal death are likely multifactorial, again showing both a need to consider cord length and low first trimester fetal blood pressure for causing low total number of helices. The author of the metanalysis cited a weakness of their study as not only variation in technique and outcomes definitions, but also a lack of “the pathophysiologic pathway that connects the abnormal UCI with the various antenatal and perinatal [sic] is not fully elucidated.” Only 6 of the 24 studies were based on antenatal measurement of coiling index usually in the second trimester ultrasound examination, however, the associations were similar to those validated by the metanalysis18.

Another metanalysis of umbilical cord lesions and neonatal outcome found fewer but similar associations. Hypocoiling was associated with preterm delivery, low Apgar scores and increased Cesarean section rate. Hypercoiling was associated with preterm delivery, increased Cesarean section rate, low birth weight, and fetal growth restriction19.

Meta-analyses merge data from differing protocols and techniques using statistical methods. However even the best evidence of statistical association may obscure some valuable details provided by an individual, well-planned study. Such a study of the coiling index was provided by Dr. de Laat and colleagues: The protocol included an initial power analysis for number of cases, appropriate blinding to outcome, definition of high CI >90th percentile and low CI < 10th percentile based on their own population, multivariate statistics, a test of concordance between the two perinatal pathologists, and precise definitions of outcome20. In such a study, it is reasonable to accept the statistically significant associations as true (of course at any level of significance there is a possibility of a false association due to chance). The study found associations of hypocoiled cords with stillbirth, spontaneous preterm birth, trisomy, low Apgar score at 5 minutes, velamentous cord insertion, single umbilical artery, and dextral handedness of the coils. Hypercoiled cords were associated with asphyxia, umbilical artery pH < 7.05, small for gestational age, trisomy, single umbilical artery, and sinistral handedness of the coils.

Potential insight from this study are: 1) The study shows the same overlap of both hypo and hypercoiling associations with outcomes of fetal hypoxia as the metanalysis with the same likely explanation, namely the possibility that the associations are secondary to the effect of growing cord length on coiling index. 2) As in the metanalysis, hypercoiled cords are associated with small for gestational age infants which as stated above could be the result of the positive correlation of the umbilical cord length and birthweight. Lighter weight infants have shorter cords and hence a higher coiling index assuming a constant number of coils from early gestation. 3) For preterm labor the results in this study differ from the metanalysis, likely because spontaneous preterm labor is specified, as it was associated only with hypocoiled cords. Since the cord length would be shorter in the preterm cords, the hypocoiled cords must be risk factor for preterm labor independent of cord length, perhaps in some way related to early fetal circulatory weakness. (The association of coiling index with preterm labor may explain the unexpected association of the index with chorioamnionitis reported in an early paper21. Preterm labor is associated with histologic chorioamnionitis) 4) That both hypo and hyper coiled cords are associated with trisomies (N = 20) and with single umbilical artery (N =19) may be related to associated malformations such as cardiovascular malformations altering initial blood flow of the helix and of hypokinesia and oligohydramnios shortening the cord length. The small number of cases in the study of these outcomes would have precluded further analysis of such factors. 5) An association of a low coiling index with velamentous cord insertion might be due to measuring the velamentous portion (that is from the separation of the vessels from the cord to the margin of the placenta). The technique of measurement of the cord with velamentous insertion was not explicitly stated. 6) This study, unlike the metanalysis, considered handedness in relation to the coiling index. The dominant sinistral (left-handed) helix was associated with hypercoiling. This hypothetically could be accounted for if a higher total blood flow difference occurs when the left umbilical artery is dominant over the right compared to right umbilical dominance.

This study found only moderate agreement between the two pathologists. This is not as helpful as knowing why they disagreed on a relatively objective task. The answer is likely to revolve around the problems in measuring the coiling index discussed in the paper by Dr. Khong6. More importantly, these disagreements could have changed the significance of some clinical associations. In the presentation of the data from the study, it would have been meaningful to see how the associations with different hypoxia related outcomes were present in specific infants, and how the individual coiling indexes for those infants compared to other infants with hyper or hypocoiled cords.

The association of coiling and fetal death

Fetal death often does not have an assigned cause, even after placental examination and autopsy. If the cause of death is to be assigned to a hypercoiled/constricted/elongated umbilical cord, then there needs to be evidence that the umbilical cord changes are not due to intrauterine postmortem twisting. In the numerous case reports and series attributing hypercoiled cords as a cause of death, the majority are second trimester fetuses, a period when there is plentiful amniotic fluid to permit postmortem rotation22-26. Reports have argued that since the cases have an increased frequency of placental lesions of fetal vascular malperfusion (FVM) the abnormal cord caused premortem blood flow obstruction. In one series, acute thrombosis of chorionic vessels was considered evidence of premortem cord constriction, but these thrombi not only need to be distinguished from postmortem clots, but also from agonal thrombi from any cause of decreased cardiac output prior to death22. This same series demonstrates the condensation of the fibrous network and loss of the gel in the Wharton’s jelly in the narrowest cross sections. Rather than being a primary lesion, this condensation could be the result of postmortem twisting that squeezed the jelly from a section of twisted cord. The lesions of FVM also need to be separated from those of prolonged postmortem retention, as the images of the reported fetal deaths often show external evidence of prolonged retention. Even if the FVM lesions were premortem, they could be a complication of premortem FVM, such as fetal cord wrapping, that was the cause of death and that preceded the postmortem twisting of the cord. As demonstrated in the discussion of the types of coiling, even thicker later gestation cords could have deep constrictions as the result of postmortem twisting. That some mothers have recurrence of the cord twisting may only be evidence that they have a recurrent, unexplained cause of second trimester death. Conceivably, an hypoxic infant would be unable to counteract the rotary currents in the uterus, and likely to develop as a secondary effect, premortem cord twisting. Until there is premortem, in vivo evidence of severe cord hypercoiling and constriction occurring prior to death, the evidence that this a primary cause of death will be moot.

Clinical significance:

If the coiling index is stable from early gestation, then this is a feature detectable by second trimester ultrasound. The coiling index has been evaluated in the second trimester to predict the onset of fetal growth restriction or preterm birth. In one prospective study, a significant association (odds ratio 3.3 (95% confidence interval 1.4–7.7, P = 0.003) was found with preterm birth but not fetal growth restriction27. However, the association was not strong enough to be useful clinically. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values for preterm birth were 47.6%, 76.9%, 9.6%, and 96.6%, respectively. Another recent prospective second trimester ultrasound study of coiling index also did not find utility28. The amount of independent additional predictive value of coiling index for labor complications and growth restriction is not established. Sequential measurements of coiling index may be a proxy for the rate of linear growth of the cord, but this inference is complicated by the different total numbers of coils per cord.

Most hypo and hypercoiled cords still have normal pregnancies and delivery. The value of a normal coil may protect the umbilical blood flow in occurrences of compression, twisting, or kinking. However, the incidence and quantitation of that potentially mitigating effect on such umbilical cord accidents is unknown.

Research:

Clinical: The discussion of the clinical correlations above, relied on the hypothesis that some correlations with outcome could be due to different lengths of the umbilical cord if the number of coils was fixed early in gestation. With 3 D ultrasound, the total number of coils and length of the cord, could be followed sequentially to test this hypothesis. Studies of the association of coiling index and outcome could be correlated with the whole cord length and total number of coils instead of the coiling index from a sample of the cord. Umbilical arterial velocities are measured by ultrasound routinely. With the addition of a perpendicular measurement of the arterial radius, a volume flow can also be calculated. Associations could be investigated of the fetal blood flow, blood velocity, coiling parameters, diameter of the umbilici cord, and fetal heart size. This approach might identify a more specific set of risk factors for fetal hypoxia. There are highly coiled long cords and short cords with few coils, that may have distinct effects on umbilical circulation. Since most infants with hypocoiled or hypercoiled cords do well, the correlations of coiling index with fetal hypoxia may be due to the differences in coiling parameters in providing protection from external vascular compression. Prenatal ultrasound examination could document any effect of vascular coiling on cord blood flow in cords that are wrapped around the fetus or compressed by a fetal part.

Basic: The development of models that are more closely match to the physiology of the umbilical vessels could provide a deeper understanding into the hemodynamic structure of the coils and of their ability to resist outside forces of compression and torsion.

References:

1. Strong TH, Jr., Jarles DL, Vega JS, Feldman DB. The umbilical coiling index. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994;170:29-32.

2. de Laat MW, Franx A, van Alderen ED, Nikkels PG, Visser GH. The umbilical coiling index, a review of the literature. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2005;17:93-100.

3. Sepulveda W, Wong AE, Gomez L, Alcalde JL. Improving sonographic evaluation of the umbilical cord at the second-trimester anatomy scan. J Ultrasound Med 2009;28:831-5.

4. Blickstein I, Varon Y, Varon E. Implications of differences in coiling indices at different segments of the umbilical cord. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2001;52:203-6.

5. Chaurasia BD, Agarwal BM. Helical structure of the human umbilical cord. Acta Anat (Basel) 1979;103:226-30.

6. Khong TY. Evidence-based pathology: umbilical cord coiling. Pathology 2010;42:618-22.

7. Subashini G, Anitha C, Gopinath G, Ramyathangam K. A Longitudinal Analytical Study on Umbilical Cord Coiling Index as a Predictor of Pregnancy Outcome. Cureus 2023;15:e35680.

8. Cromi A, Ghezzi F, Durig P, Di Naro E, Raio L. Sonographic umbilical cord morphometry and coiling patterns in twin-twin transfusion syndrome. Prenat Diagn 2005;25:851-5.

9. Bamberg C, Diemert A, Glosemeyer P, Tavares de Sousa M, Hecher K. Discordance of umbilical coiling index between recipients and donors in twin-twin transfusion syndrome. Placenta 2019;76:19-22.

10. Lacro RV, Jones KL, Benirschke K. The umbilical cord twist: origin, direction, and relevance. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1987;157:833-8.

11. Ernst LM, Minturn L, Huang MH, Curry E, Su EJ. Gross patterns of umbilical cord coiling: correlations with placental histology and stillbirth. Placenta 2013;34:583-8.

12. Khong TY, Mooney EE, Ariel I, et al. Sampling and Definitions of Placental Lesions: Amsterdam Placental Workshop Group Consensus Statement. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2016;140:698-713.

13. Genest DR. Estimating the time of death in stillborn fetuses: II Histologic evaluation of the placenta: a study of 71 stillborns. Obstet Gynecol 1992;80:585-92.

14. Dado GM, Dobrin PB, Mrkvicka RS. Venous flow through coiled and noncoiled umbilical cords. Effects of external compression, twisting and longitudinal stretching. J Reprod Med 1997;42:576-80.

15. Georgiou HM, Rice GE, Walker SP, Wein P, Gude NM, Permezel M. The effect of vascular coiling on venous perfusion during experimental umbilical cord encirclement. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001;184:673-8.

16. Kaplan AD, Jaffa AJ, Timor IE, Elad D. Hemodynamic analysis of arterial blood flow in the coiled umbilical cord. Reprod Sci 2010;17:258-68.

17. Wilke DJ, Denier JP, Khong TY, Mattner TW. Estimating umbilical cord flow resistance from measurements of the whole cord. Placenta 2021;103:180-7.

18. Mittal A, Nanda S, Sen J. Antenatal umbilical coiling index as a predictor of perinatal outcome. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2015;291:763-8.

19. Hayes DJL, Warland J, Parast MM, et al. Umbilical cord characteristics and their association with adverse pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2020;15:e0239630.

20. de Laat MW, Franx A, Bots ML, Visser GH, Nikkels PG. Umbilical coiling index in normal and complicated pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:1049-55.

21. Machin GA, Ackerman J, Gilbert-Barness E. Abnormal umbilical cord coiling is associated with adverse perinatal outcomes. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2000;3:462-71.

22. Peng HQ, Levitin-Smith M, Rochelson B, Kahn E. Umbilical cord stricture and overcoiling are common causes of fetal demise. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2006;9:14-9.

23. AK K, HM P, ALS G, et.al. Umbilical cord constriction as a cause of intrauterine fetal death. J Bras Patol Med Lab 2021;57:1-5.

24. Slack JC, Boyd TK. Fetal Vascular Malperfusion Due To Long and Hypercoiled Umbilical Cords Resulting in Recurrent Second Trimester Pregnancy Loss: A Case Series and Literature Review. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2021;24:12-8.

25. Hersh JH, Buchino J. Umbilical cord torsion/constriction sequence. In: Sual R, editor. Proceedings of the Greenewood Genetics Conference; 1988. p. 181-2.

26. Manjee K, Price E, Ernst LM. Comparison of the Autopsy and Placental Findings in Second vs Third Trimester Stillbirth. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2023;26:345-51.

27. Ndolo JM, Vinayak S, Silaba MO, Stones W. Antenatal Umbilical Coiling Index and Newborn Outcomes: Cohort Study. J Clin Imaging Sci 2017;7:21.

28. Singireddy N, Chugh A, Bal H, Jadhav SL. Re-evaluation of umbilical cord coiling index in adverse pregnancy outcome – Does it have role in obstetric management? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X 2024;21:100265.