Umbilical cord length: Short and long cords

The diagnosis of long or short umbilical cord

Measuring the true length of the umbilical cord is best done by the clinical team as some segments of the cord may not be received in pathology such as segments left attached to the infant, for example after cutting for a tight nuchal cord, or handing off a very distressed infant to the neonatologist, or segments removed for blood gases or research. These segments may or may not be submitted with the placental specimen. In the pathology laboratory, we measure what we receive. The pathology diagnosis of a long cord is valid even if the true length was longer, but some normal length cords in pathology have been long cords in situ. Likewise, a short cord in pathology cannot be shorter than in situ but may be just a segment of a normal or even long cord.

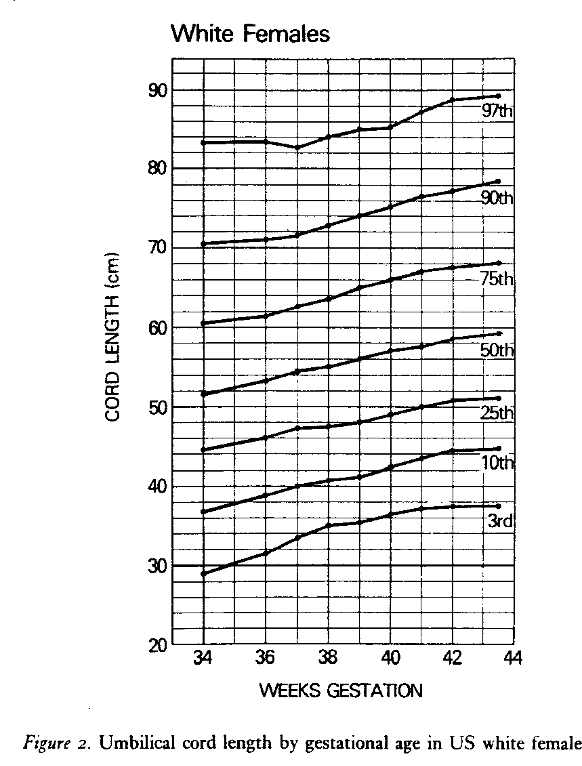

Across international studies, the umbilical cords of term infants average 50-60 cm in length1-7. The umbilical cord grows throughout gestation, yet between 34 and 42 weeks of gestation the mean usually is within this range, example figure below1.

The mean length is longer the greater the birth weight and this relationship also holds for other variables directly related to birthweight such as maternal weight, maternal weight gain during pregnancy, placental weight. and male sex of the infant3. These relationships may not be true in different populations as a prospective study of 1,000 pregnancies from India did not find a significant association between cord length and birthweight or sex of the infant8. Published norms of umbilical cord length vary by whether they are based on clinical measures of the whole cord or on the cord received in pathology. To complicate matters even more, the umbilical cord can shrink a mean of 3.5 cm, 23 hours after delivery9. Fortunately, as a practical matter, designating the length as pathologically short or long is based on the extremes of the distribution that are little effected by fetal weight and gestation, except for those from early gestation. A short cord is usually diagnosed when the length is less than 35 cm, roughly below the 10th percentile. This length corresponds to an adequate length of cord to reach from a fundal implantation of the cord to the introitus, allowing the fetus to deliver with the placenta still attached to the uterine wall. A low-lying placenta may only require 22 cm of cord for a vaginal delivery. A long cord, above the 90th percentile, usually falls at >70 cm.

Midgestational stillbirths often have thin, long, and twisted umbilical cords10,11. The report of 3 recurrent stillbirths of one mother that had long, twisted cords and placental histology of fetal vascular malperfusion does not prove that this is necessarily a genetic syndrome10. An alternative explanation is that a fetus dying in mid-gestation of any cause may suffer the cord changes as a passive postmortem event. At this gestation, the fetus is suspended in sufficient amniotic fluid that passive stretching could lead to lengthening and thinning of the cord. As will be demonstrated in the chapter on fetal coiling index, maternal movement could also lead to passive twisting of the cord.

The diagnostic value of a long or short cord:

Both long and short cords have been associated with various obstetrical complications. Even from early modern obstetrical studies of cord length, the surprising finding was that the complications associated with very short and long cords were similar. “Inadequate fetal descent was significantly more common when a long cord or an excessively short cord (25 cm of less, lower first percentile), was found. Fetal heart rate (FHR) abnormalities that primarily reflected cord compression were significantly more frequent in the presence of a short (17 of 27 cases, 63%) or al long cord (28 of 32 cases, 87%) as compared with a normal length cord (145 of 393 cases 37%)” 2 One explanation is that the long cords are wrapped cords, and that the fetus was left with a only a short length of free cord that was equivalent to an anatomically short cord. A subsequent study demonstrated that arterial blood cases were not abnormal in most infants with a long or short umbilical cord12. However, if the fetus also had severe deep variable FHR decelerations or bradycardia, then an umbilical blood pH below 7.2 was found with 2 of 61 short cords and 5 of 111 long cords. This finding suggests that it is not the length of the cord per se that causes fetal complications, but that under certain conditions the length predisposes to fetal hypoxia/ acidosis and to potential fetal death or neurologic injury. Those conditions such as wrapping, compression, kinking, and torsion of the cord will be discussed in another post on the fetal circulation as a component of the placental system, and its potential for failure.

Short cords:

Short umbilical cords can result from both experimental and clinical fetal paralysis13-15. This observation led to the hypothesis that fetal movement puts tension on the cord that stimulates linear growth. This topic will be discussed further under the basic science of cord growth below. This hypothesis predicts that a short cord can be a diagnostic indicator of neurologic, neuromuscular or muscle disease that decreases fetal movement or of conditions that restrict movement in utero. Smith and colleagues proposed the term fetal hypokinesia/akinesia sequence for the cluster of consequences of fetal paralysis which included short umbilical cord, pulmonary hypoplasia, and limb deformities, which are often severe and termed arthrogryposis congenita multiplex. The experimental rat model used curare to paralyze the fetus The same sequence of features in human infants were found with a variety of causes of paralysis including maternal treatment with curare for tetanus16, fetal spinal muscular dystrophy17, and anti-neuromuscular junction antibodies that crossed the placenta from mothers with myasthenia gravis18. The explanatory power of this sequence elucidated the Pena-Shokeir syndrome which had the akinesia sequence features associated with brain abnormality19.

Severe akinesia sequence is often lethal or clinically severe irrespective of the specific etiology. Documenting a short umbilical cord is confirmatory evidence of an intrauterine origin of the infant’s motor disease. Reasonably, hypokinesia might cause a less severe sequence with a less severe shortening of the umbilical cord. The experimental effect of a 35 % alcohol diet in maternal rats produces decreased fetal movement, and results in significantly shorter cords compared to controls20. One study using the cord lengths obtained in the Perinatal Collaborative Project found evidence that infants with trisomy 21, who typically are hypotonic in the nursery, had a significantly shorter average cord length, 45.1, compared to 57.3 for matched controls21. Shorter cords in rats were also found with maternal cocaine administration22. The diagnostic value of a short umbilical cord as an indicator of hypokinesia and a predictor of prenatal neurologic disease in cases that do not show immediate neonatal disease remains to be fully investigated.

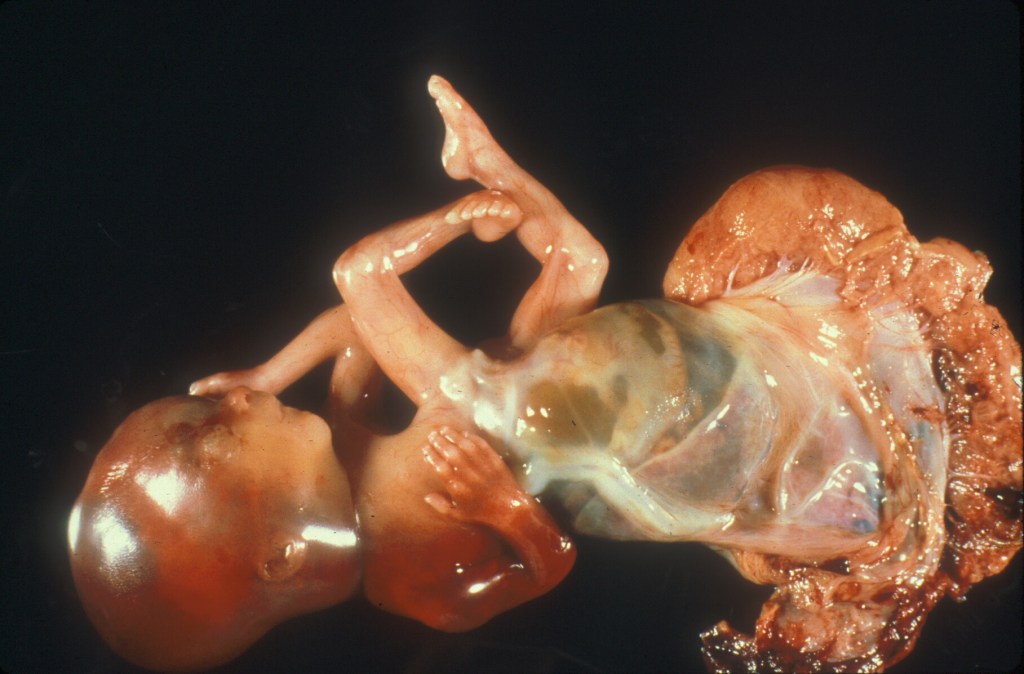

Physical restraint in a neurologically intact fetus can also cause hypokinesia/ akinesia sequence23. The most severe causes of short cord with intrauterine restraint are those associated with fetal adhesion to the placenta as in limb body wall defects and in early amnion rupture sequence24.

Figure 2 Limb body wall defect with very short umbilical cord

Some infants who lack amniotic fluid (oligo- or anhydramnios) may have a short cord from restricted movement from contraction of the intrauterine volume in which to move. Not all cases of oligohydramnios are associated with a short cord. In one study 10 cases with renal agenesis, who therefore had no fetal urine and as a result had early onset anhydramnios, had cord lengths that were below 25 cm long from 20 to 38 weeks of gestation25. Some other causes of oligohydramnios in that study who had longer cords may have had later onset or incomplete loss of urine output, for example with posterior urethral valve obstruction or Enalapril induced renal tubular dysgenesis.

Umbilical cords that are too short to allow normal descent of the fetus in labor while the placenta is attached to the uterine wall may demonstrate abnormal fetal heart tracing, require Cesarean section for arrest of fetal descent, or even cause a premature placental separation during delivery. A retrospective study of 80 cases of infants given in utero amnioinfusion for abnormal fetal heart rate tracings, predominantly persistent deep variables (a marker of cord compression), found that twelve infants still required a Cesarean section because of continued abnormal fetal heart rate26. This group had a statistically shorter umbilical cord. Seven of the Cesarean sectioned infants had nuchal cords. Wrapping an already short cord around the body creates an even shorter effective cord length. In a study of 5,885 deliveries, a cord less than 40 cm was associated with a greater incidence of operative delivery (forceps or Cesarean section)27. The authors’ discussion section noted that a loop of a short cord around the fetus would be more likely to be too short for delivery than with a longer cord. They suggested that a lack of correlation with compromised fetal outcome in some studies of cord length could be due to fetal monitoring leading to an operative delivery preventing complications from vaginal delivery. Many of the “short” cords in the above studies were not too short to allow delivery, so either they were further looped around the fetus shortening the free length, or they were compromising umbilical blood flow in another way. A short cord could theoretically decrease umbilical blood flow by being stretched during delivery thus increasing pressure on the vessels28, or being more susceptible to cord torsion from fetal rotation29.

The bottom line is that short cords may: 1) be a consequence of a fetal abnormality and those cases may also have other features of the hypokinesia sequence, such as limb deformity or pulmonary hypoplasia 2) physically tether the fetus from traversing the path to a normal vaginal delivery, or 3) or in less understood ways, compromise umbilical blood flow. The latter two effects may be exacerbated by wrapping of the short cord around the fetus. Such cord wrapping occurs with normal movement of the fetus and perhaps would be less likely in the more severely paralyzed infants.

Long cords:

If decreased fetal movement causes short cords, does fetal hyperactivity cause long cords? The evidence is not conclusive. In experimental studies in the rat, early gestational delivery into the abdominal cavity led to longer cords. The presumed explanation was increased fetal activity in the large abdominal space. A study of 62 women who had home devices that recorded fetal movement from maternal abdominal movement demonstrated that the only significant relationship of increased fetal movement with long cords (>60 cm) occurred only in the gestational interval from 36 to 39 weeks of gestation, and not at other gestations and cord lengths30. The authors had previously demonstrated that movement normally decreases in this late gestation time interval, but this occurs less in infants who develop long cords. The cause of hyperactivity in the infants was not investigated, nor the long-term outcome.

Another cause of long cords follows an evolutionary argument. If fetal wrapping commonly shortens the free length between the placenta and the wrapped infant, then reproductive success depends on a mechanism to increase that free length to allow a normal delivery.

Figure 3 Multiple umbilical cord wrappings of a fetus delivered en caul showing the very short amount of free cord from the placental insertion to the fetal wrapping.

The tension on the newly short cord might stimulate the same mechanism to re-lengthen the cord to an adequate length as occurs during natural growth. The success of this compensatory lengthening would likely depend on how much cord length is lost to the wrapping around the fetus and when the wrapping occurred prior to delivery of the infant. Evidence in favor of this hypothesis is that long cords have been associated with cord abnormalities such as knots and nuchal cords that are evidence of cord wrapping. After delivery, the measured cord length would include the lengths of the wrapped cord and of the free cord (that is the cord between the last wrap and the placenta which would be stretched by fetal movement). An example of the additive effect of a cord wrapping to a normal cord length is demonstrated by multiple nuchal cord wrappings in a study of 1,000 pregnancies8:

# of loops # of cases mean umbilical cord length

| One loop | 124 | 65±15 |

| Two loops | 78 | 84±15 |

| Three loops | 15 | 95±15 |

| Four loops | 2 | 100±15 |

| Five loops | 1 | 110 |

A long cord has been associated with a long list of obstetrical complications. As already mentioned, some of these are the same as with short cord and this concordance may be the result of the creation of a functionally short cord when the wrapping occurs.

A comprehensive retrospective study of long cords (926 patients with cords ≥ 70 cm for gross pathologic and clinical review, and 129 for placental for microscopic review) found significant associations when compared to controls: those expected to be found: placenta weight, and male sex11; those attributable to fetal hypoxia: asphyxia at birth, low Apgar scores, delivery complications, meconium macrophages in the fetal membranes, and non-reassuring fetal status; those associated with cord wrapping: cord knots, cord twisting, and abnormal presentation; those with microscopic features consistent with compromised fetal blood flow: fetal vascular thrombi, intimal cushions and chorangiosis (villous capillary proliferation); and those with more complex outcomes without simple interpretations: maternal disease, fetal anomalies, and increased syncytial knots (a likely response to maternal under perfusion of the placenta). Long cords more generally have been associated with histological placental features of fetal vascular malperfusion31. Other studies have associated long cords with stillbirth or neurologic injury although studies are sometimes contradictory. A recent meta-analysis of umbilical cord lesions associated with stillbirth rejected including the analysis of cord length because of the lack of uniformity in the diagnosis of abnormal length32.

It is not clear that a long cord is intrinsically at greater risk for becoming entangled by fetal movement than a shorter length of cord. However, if increasing cord length increased the chance of fetal cord wrapping, then this would provide an alternative hypothesis to compensatory growth to explain the association of long cords with cord knots, nuchal cords, and other evidence of wrapping. This hypothesis would require that long cords were caused by innate factors such as fetal size, genetics, and hyperactivity. If this hypothesis were true, then some causes of hypermobility in utero might present as neurological deficits after delivery. Longitudinal imaging studies during pregnancy of the cord length, fetal movement, and intrauterine cord entanglement may be able to resolve which of these two hypotheses is true.

Fluid resistance in rigid tubes with Newtonian flow conditions is directly related to length. The umbilical cord likely meets none of these criteria, and in any case increasing the diameter of the cord vessels could compensate to lower the resistance. It is unlikely that the cord length causes clinically significantly increased resistance compared to normal cord lengths even considering the increase length from the vascular helix of the cord. There is a more complex theoretical basis that suggests long twisted cords may increase mural shear stress, but this also does not seem to explain the increased risk of hypoxia with longer cords, especially as most long cords to not have compromised infant outcomes.

Unlike the tethering effect of short cords, the evidence of direct harm from long cords (that are not “short” cords due to wrapping) is less certain. There are some older papers that identified long cords as increasing the risk of umbilical cord prolapse, but recent papers have concentrated on stronger risk factors for prolapse such as polyhydramnios (more room to move) and non-vertex fetal presentation (possible complex cord entanglement) which might be associated with longer cords33.

Practical pathology

The pathology report can only record the length of the cord received. Ideally, the clinical history should record the full length. A true short cord may have explanatory value, for example of the need for an operative delivery. In medical legal cases, the short cord may be useful evidence supporting an early origin of a neurological injury. A clear standard for the institution for measuring and recording fetal cord length would make the information more useful in clinical studies.

There is no receiver operator optimum cut off determined for short or long cords. Diagnostic cut offs for short or long cords based on percentiles or standard deviations might need to be adjusted for gestational age, birthweight, and fetal sex. The short cord cut off to predict arrest of labor may depend on the distance the fetus must traverse. A short cord cut off to predict fetal hypokinesia may depend on a continuous relationship between fetal movement and cord length. A short cord cut off to predict deep variable fetal heart rate decelerations, or stillbirth may have a stochastic relationship to the chance of fetal cord wrapping. As a rough screening tool, our current criteria are less than 35 cm for a short cord, and more than 70cm for a long cord.

Routine histological sampling of the umbilical cord normally included a fetal and, a placental end section. This sampling protocol is done because cord pathology is not always uniform, for example a patent urachus would be evident at the fetal end, but acute funisitis may be more intense at the placental end.

Research potential related to umbilical cord length:

Basic Science: The umbilical cord has a simple structure. It is without a capillary bed, has a helical collagenous structure firmly attached to the vessels and surface, and has a colloid glycosaminoglycan matrix full of fibroblasts, primitive stem cells and some mast cells. Longitudinal tugging on the cord appears to initiate growth. Such growth needs to be modulated between two evolutionary goals for reproductive survival, primarily having a cord long enough to safely deliver a viable infant even if wrapped around its body parts, and secondarily not to overshoot the length potentially wasting nutrients, and potentially increasing fetal entanglement, and vascular resistance. How this feat is accomplished seems ripe for some basic discoveries. How does the coiled structure of the cord respond to longitudinal tension and the release of active growth factors? How is this stimulus damped down if the tension is transient?

Viable human umbilical cords are a readily available specimen. A study using immunohistochemistry for “growth and apoptotic” factors on 31 umbilical cords from stillborn infants who had a wide array of other findings and cord lengths found differences in expression, but little clarity34. Definitive experiments could be conducted on segments of human umbilical cord that are viable and perfused with needed oxygen and nutrients. Then the molecular effects of stretching, twisting, hypoxia and blood pressure could be investigated directly.

Clinical Science: With the advent of 3D ultrasound and with MRI techniques, the cord length can be surveyed and measured during the pregnancy to study changes in length and the relationship to wrapping, and other complications such as prolapse or possibly premature placental separation35,36. The cord length could be directly related to fetal movement, to placental insertion site in the uterus, and to Doppler hemodynamics. Prepartum studies of the actual and the free cord length may find stronger predictors of the risk of stillbirth, perinatal asphyxia, or delivery due to non-reassuring fetal heart tones. The specific anatomic causes of deep variable fetal heart rate decelerations associated with long or short cords could be taken out of the “black box”, and become visible, and potentially treatable if such imaging were available during labor.

References

1. Mills JL, Harley EE, Moessinger AC. Standards for measuring umbilical cord length. Placenta 1983;4:423-6.

2. Rayburn WF, Beynen A, Brinkman DL. Umbilical cord length and intrapartum complications. Obstet Gynecol 1981;57:450-2.

3. Naeye R. Umbilical cord length: clinical significance. J Pediatr 1985;107:278-81.

4. Sarwono E, Disse WS, Oudesluys Murphy HM, Oosting H, De Groot CJ. Umbilical cord length and intra uterine wellbeing. Paediatr Indones 1991;31:136-40.

5. Malpas P. Length of the Human Umbilical Cord at Term. Br Med J 1964;1:673-4.

6. Adinma JI. The umbilical cord: a study of 1,000 consecutive deliveries. Int J Fertil Menopausal Stud 1993;38:175-9.

7. Agboola A. Correlates of human umbilical cord length. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1978;16:238-9.

8. Shiva Kumar HC, Chandrashekhar T. Tharihalli, Chandrashekhar K., Suman F. Gaddi. Study of length of umbilical cord and fetal outcome: a study of 1000 deliveries. International Journal of Reproduction, Contraception, Obstetrics and Gynecology 2017;6:3770-5.

9. Manci EA, Alvarez SS, McClellan SB, et al. Biphasic Postnatal Umbilical Cord Shortening. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2021;24:116-20.

10. Slack JC, Boyd TK. Fetal Vascular Malperfusion Due To Long and Hypercoiled Umbilical Cords Resulting in Recurrent Second Trimester Pregnancy Loss: A Case Series and Literature Review. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2021;24:12-8.

11. Baergen RN, Malicki D, Behling C, Benirschke K. Morbidity, mortality, and placental pathology in excessively long umbilical cords: retrospective study. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2001;4:144-53.

12. Berg TG, Rayburn WF. Umbilical cord length and acid-base balance at delivery. J Reprod Med 1995;40:9-12.

13. Miller ME, Jones MC, Smith DW. Tension: the basis of umbilical cord growth. J Pediatr 1982;101:844.

14. Moessinger AC, Blanc WA, Marone PA, Polsen DC. Umbilical cord length as an index of fetal activity: experimental study and clinical implications. Pediatr Res 1982;16:109-12.

15. Moessinger A. Fetal akinesia deformation sequence: an animal model. Pediatrics 1983;72:857-63.

16. Jago RH. Arthrogryposis following treatment of maternal tetanus with muscle relaxants. Arch Dis Child 1970;45:277-9.

17. Kizilates SU, Talim B, Sel K, Kose G, Caglar M. Severe lethal spinal muscular atrophy variant with arthrogryposis. Pediatr Neurol 2005;32:201-4.

18. Smit LM, Barth PG. Arthrogryposis multiplex congenita due to congenital myasthenia. Dev Med Child Neurol 1980;22:371-4.

19. Lavi E, Montone K, Rorke L, Kliman H. Fetal Akinesia Deformation Sequence (Pena-Shokeir Phenotype) Associated with Acquired Intrauterine Brain Damage. Neurology 1991;41:1467-8.

20. Barron S, Riley EP, Smotherman WP. The effect of prenatal alcohol exposure on umbilical cord length in fetal rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1986;10:493-5.

21. Moessinger AC, Mills JL, Harley EE, Ramakrishnan R, Berendes HW, Blanc WA. Umbilical cord length in Down’s syndrome. Am J Dis Child 1986;140:1276-7.

22. Barron S, Foss JA, Riley EP. The effect of prenatal cocaine exposure on umbilical cord length in fetal rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol 1991;13:503-6.

23. Miller M, Higginbottom M, Smith D. Short umbilical cord: Its origin and relevance. Pediatr 1981;67:618-21.

24. Kalousek DK, Bamforth S. Amnion rupture sequence in previable fetuses. Am J Med Genet 1988;31:63-73.

25. Izumi K, Jones KL, Kosaki K, Benirschke K. Umbilical cord length in urinary tract abnormalities associated with oligohydramnios: evidence regarding developmental pathogenesis. Fetal Pediatr Pathol 2006;25:233-40.

26. Iwagaki S, Takahashi Y, Chiaki R, et al. Umbilical cord length affects the efficacy of amnioinfusion for repetitive variable deceleration during labor. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2022;35:86-90.

27. Sornes T. Short umbilical cord as a cause of fetal distress. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1989;68:609-11.

28. Pennati G. Biomechanical properties of the human umbilical cord. Biorheology 2001;38:355-66.

29. Bendon RW, Brown SP, Ross MG. In vitro umbilical cord wrapping and torsion: possible cause of umbilical blood flow occlusion. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2014;27:1462-4.

30. Ryo E, Kamata H, Seto M, Morita M, Yatsuki K. Correlation between umbilical cord length and gross fetal movement as counted by a fetal movement acceleration measurement recorder. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X 2019;1:100003.

31. Ma LX, Levitan D, Baergen RN. Weights of Fetal Membranes and Umbilical Cords: Correlation With Placental Pathology. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2020;23:249-52.

32. Hayes DJL, Warland J, Parast MM, et al. Umbilical cord characteristics and their association with adverse pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2020;15:e0239630.

33. Lin MG. Umbilical cord prolapse. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2006;61:269-77.

34. Olaya CM, Fritsch M, Bernal JE. Immunohistochemical protein expression profiling of growth- and apoptotic-related factors in relation to umbilical cord length. Early Hum Dev 2015;91:291-7.

35. Collins JH. The Case for Umbilical Cord Screening Via Ultrasound at 18–20 Weeks. Med Res Arch 2021;9:1-10.

36. Katsura D, Takahashi Y, Shimizu T, et al. Prenatal measurement of umbilical cord length using magnetic resonance imaging. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2018;231:142-6.