Dr. Altshuler’s brief often cited paper in 1984 gave a precise definition of chorangiosis [1]. Despite the definition’s fame as a series of tens, the definition is somewhat arbitrary* and the clinical correlations nebulous. Chorangiosis has become an accepted name for a pathological observation that in some form certainly exists. An earlier paper by Caldwell et. al. attributes what seem to be the first English use of the term, chorangiosis, to a personal communication with Dr. Shirley Driscoll[2]. I may be an outlier, but I am still uncertain what chorangiosis implies as a diagnosis.

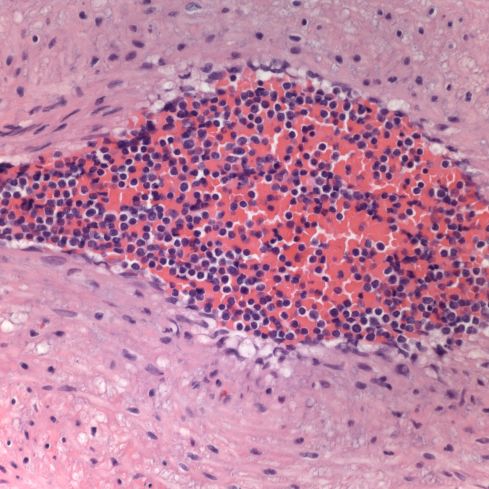

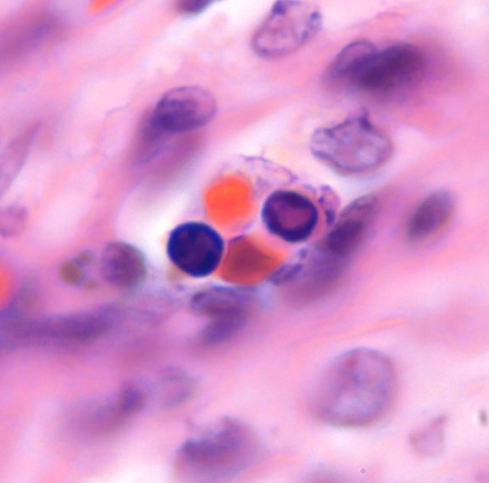

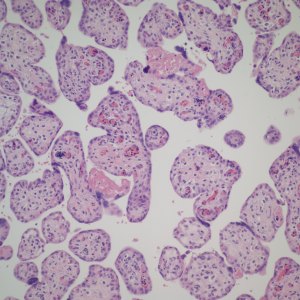

First I have trouble distinguishing hypervascularity in the villi from congestion which likely increases the apparent number of capillaries seen in microscopic cross section of a villus due to folding of engorged capillaries. Dr. Altshuler’s paper, warned of possible confusion between the two, and provided an illustration. Looking at his comparison photomicrograph in the paper I count at least 6 villi with more than 10 vascular profiles in the congested villi example. Given a photograph from a different area, that case might have qualified as chorangiosis. Many of the published papers illustrating chorangiosis in fact show villi with very dilated capillaries that do not give me confidence in the diagnosis[3-5]. To quote from a case review of chorangiosis: “Therefore, rigid diagnostic criteria were established by Altshuler (1984) for diagnosis of CH. These criteria, though difficult to apply, aim at differentiating CH from congestion(vessels numerically normal) and tissue ischemia (shrinkage of villi)…[6]”. The underline is mine. The acute capillary dilatation and probably increased blood flow over a retroplacental hemorrhage appears to increase the number of capillaries (fig) 1. This may explain the reported association of chorangiosis and abruption[7]. Perhaps congested villi with apparent hypervascularity should tentatively be a separate entity.

Dilated villous capillaries above a retroplacental hematoma

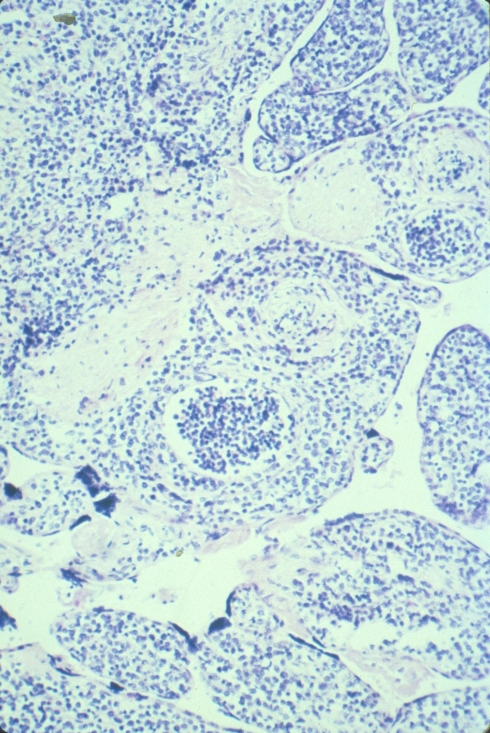

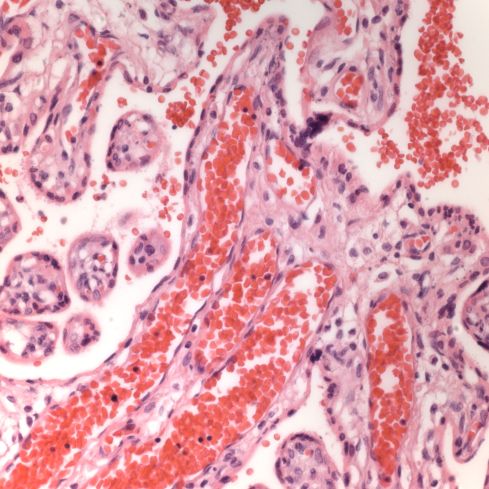

Distinguishing chorangiosis with its large terminal villi from persistent or increased intermediate villi is also not simple. I suspect that this confusion may be responsible for the association of maternal diabetes and chorangiosis. Dr. Ogino and Redline’s paper specifically mentions that the association is also with placentomegaly and delayed villous maturation. This problem can be seen clearly in looking at very early gestation placentas. (fig 2)

Placental villi from an aborted Potter syndrome fetus at 23 weeks gestation

Another problem is to distinguish chorangiosis from diffuse chorangioma (chorangiomatosis), which was amply clarified in the same Orgino and Redline paper. Yet this confusion persists, at least in the titles, in some publications [8, 9].

Chorangiosis currently does not imply a distinct pathogenesis. The associations in Dr. Altshuler’s paper were with very broad clinical categories, things like neonatal death 39% positive, anomalies 27% positive, and Cesarean section (32%). The significance of the high percentages must be tempered by the fact that the placentas were examined for obstetrical indications. Dr. Altshuler states that “My hospital rarely encounters it in normal pregnancies.” This is less than valid statistical analysis.

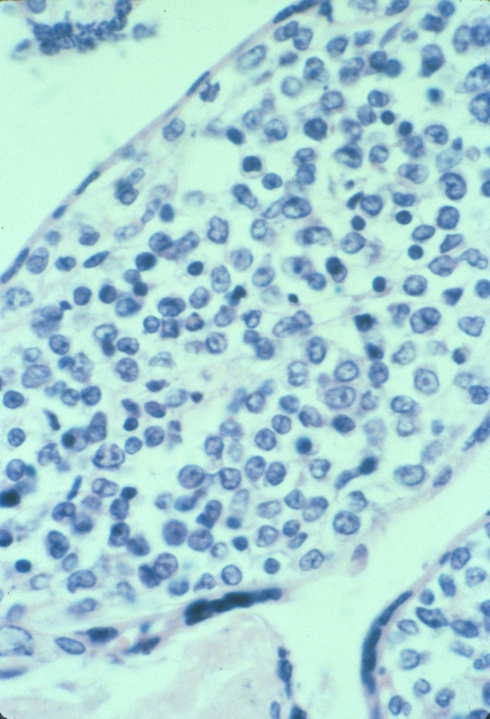

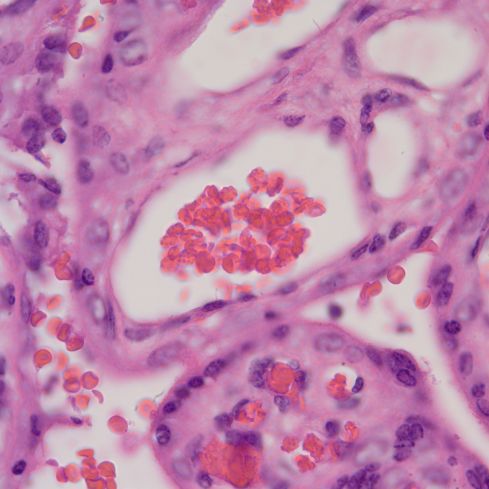

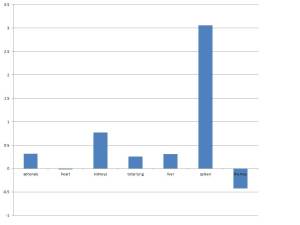

Altshuler’s paper found that 27% of cases had villitis of unknown etiology. This is certainly a finding that routine placental examination appears to support (fig 3). In practice, if I see a focus of larger, hypervascular villi, this is a clue to look for villitis and avascular villi. I rationalize this hypervascularity as due to increased blood flow in a segment of a stem villus in which other segments have capillary occlusion. The villi with shunted blood flow adapt over time by producing more capillaries. A similar adaption to high flow can be seen in diffuse hypervascularity of villi in the recipient twin in twin-to-twin-transfusion in which the pregnancy was prolonged with serial amniocentesis[10].

Lympho-histiocytic villitis and hypervascular villi

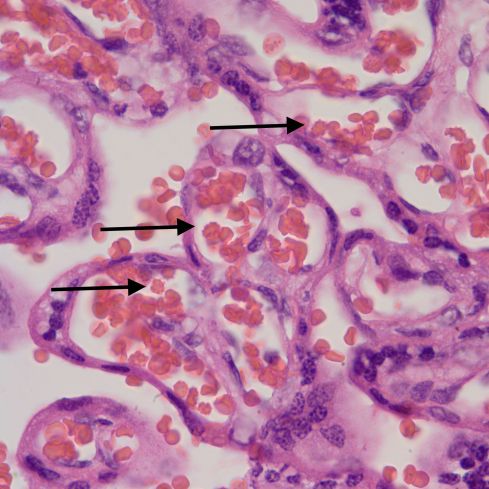

In a previous blog I have discussed the papers by Mana Parast and colleagues associating umbilical cord occlusion with fetal vascular thrombi and avascular villi [11-13]. If focal chorangiosis accompanies such avascular villi this might explain the association with Cesarean section if they were performed for fetal distress. Some have found cases of chorangiosis with umbilical cord abnormalities, for example tight nuchal cord[14]. Such a relationship could tie avascular villi, chorangiosis and poor fetal outcomes together, but it would need to be tested. Even so, a reasonable first draft might separate focal hypervascular villi associated with villitis or avascular villi as a separate entity from a diffuse form.

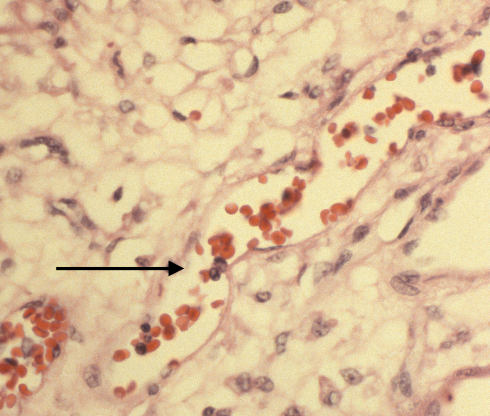

While some have suggested chronic hypoxia as a cause of chorangiosis, I think that is unlikely for two reasons [4, 5, 15-17]. First I don’t see hypervascular villi with chronic utero-placental ischemia even in stillborn infants, many of whom likely had become hypoxic. Second, increasing the capillaries does not necessarily increase oxygen transport to the fetus. See Mayhew and colleagues discussion of the relative role of parameters of oxygen transfer in the placenta[18]. Keeping most parameters within physiological limits, the only important variable is the thickness of the barrier between the maternal and fetal circulation. Another possible mechanism of chorangiosis is a varicose vein of the villi mechanism in which back venous pressure is the cause. I think this is unlikely since the usual effect of elevated umbilical venous pressure is hydrops. A third theory is a genetic or acquired mismatch in growth factors, e.g. witness the extreme capillary proliferation in mesenchymal dysplasia of the placenta of which one cause is the imprinting error in Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. There is a case report of chorangiosis associated with elevated maternal HCG late in pregnancy[19], which may be a clue to a type of mechanism. The following figure 4 shows the abrupt onset of capillary proliferation from a stem villus in a placenta submitted for “probably Down Syndrome” that might have a genetic basis.

Normal stem villus with attached branch showing capillary proliferation

The very concept of chorangiosis suggests a mismatch between capillary and villous growth. Growth factors favoring endothelial proliferation are likely involved. New branching would not be necessary since stuffing a longer capillary in the villus is likely to curl up and increase capillaries per cross section. However, there could be differences in the three dimensional anatomy of the blood vessel growth that would be difficult to discern in a microscope section, and such differences might reflect some aspects of pathogenesis.

I recently tried to look at a placenta with diffuse villous hypervascularity under the dissecting scope( fig 5,6,7). I wanted to compare my case to the classical SEM corrosion casts of villous capillaries but without the work[20]. It was a total disappointment. After fixation the blood was not visible in the capillary vessels. This case is interesting because the placenta was submitted to pathology by an obstetrician who submits all placentas even without a specific obstetrical problem. The infant was an AGA 39 week vaginal delivery with Apgars of 8 and 9 at 1 and 5 minutes without recorded complications. However the placenta weighed 790 g for a very abnormal fetal placenta weight ratio of 4.3, reflecting the abnormal villi.

Diffuse increased vascularity

Diffuse increased vascularity

Dissecting scope of same hyerpvascular villi

I diagnosed the above case as a mature placenta with hypervascular villi. I commented that the significance of the lesion is unknown.

Bottom Line In general I think the criteria of Altshuler are too inclusive and prone to overlap normal cases especially with villous congestion, so I do not make a diagnosis “chorangiosis”.I propose a tenative reclassification of “Altshuler’s lesion”1. Focal hypervascular villi associated with villitis2. Focal hypervascular villi associated with avascular villi3. Hypervascular villi with marked capillary dilatation4. Hypervascular villi associated with delayed villous maturation5. Diffuse hypervascular villi without other features. At this point I think the diagnosis should depend on a clear separation from any normal distribution of villous capillaries, but I don’t have a simple forumula. I look forward to any disagreements, suggestions or examples.

Bob Bendon

*“Chorangiosis was diagnosed when inspection with a 10x objective showed tem villi, each with ten or more vascular channels in ten of more non-infarcted and non-ischemic zones of at least three different placental areas.”

References:

1. Altshuler, G., Chorangiosis. An important placental sign of neonatal morbidity and mortality. Arch Pathol Lab Med, 1984. 108(1): p. 71-4.

2. Caldwell, C., et al., Chorangiosis of the placenta with persistent transitional circulation. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1977. 127(4): p. 435-6.

3. De La Ossa, M.M., B. Cabello-Inchausti, and M.J. Robinson, Placental chorangiosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med, 2001. 125(9): p. 1258.

4. Soma, H., Y. Watanabe, and T. Hata, Chorangiosis and chorangioma in three cohorts of placentas from Nepal, Tibet, and Japan. Reprod Fertil Dev, 1995. 7(6): p. 1533-8.

5. Akbulut, M., et al., Chorangiosis: the potential role of smoking and air pollution. Pathol Res Pract, 2009. 205(2): p. 75-81.

6. Gupta, R., et al., Clinico-pathological profile of 12 cases of chorangiosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet, 2006. 274(1): p. 50-3.

7. Staribratova, D. and N. Milchev, [Placental chorangiosis associated with abruption and hypoxia]. Akush Ginekol (Sofiia), 2009. 48(5): p. 44-6.

8. Caldarella, A., A.M. Buccoliero, and G.L. Taddei, Chorangiosis: report of three cases and review of the literature. Pathol Res Pract, 2003. 199(12): p. 847-50.

9. Schmitz, T., et al., Severe transient cardiac failure caused by placental chorangiosis. Neonatology, 2007. 91(4): p. 271-4.

10. Pietrantoni, M., et al., Mortality conference: twin-to-twin transfusion [clinical conference]. J Pediatr, 1998. 132(6): p. 1071-6.

11. Tantbirojn, P., et al., Gross abnormalities of the umbilical cord: related placental histology and clinical significance. Placenta, 2009. 30(12): p. 1083-8.

12. Parast, M.M., C.P. Crum, and T.K. Boyd, Placental histologic criteria for umbilical blood flow restriction in unexplained stillbirth. Hum Pathol, 2008. 39(6): p. 948-53.

13. Ryan, W.D., et al., Placental histologic criteria for diagnosis of cord accident: sensitivity and specificity. Pediatr Dev Pathol, 2012. 15(4): p. 275-80.

14. Franciosi, R.A., Placental pathology casebook. Chorangiosis of the placenta increases the probability of perinatal mortality. J Perinatol, 1999. 19(5): p. 393-4.

15. Schwartz, D.A., Chorangiosis and its precursors: underdiagnosed placental indicators of chronic fetal hypoxia. Obstet Gynecol Surv, 2001. 56(9): p. 523-5.

16. Suzuki, K., et al., Chorangiosis and placental oxygenation. Congenit Anom (Kyoto), 2009. 49(2): p. 71-6.

17. Barut, A., et al., Placental chorangiosis: the association with oxidative stress and angiogenesis. Gynecol Obstet Invest, 2012. 73(2): p. 141-51.

18. Mayhew, T.M., M.R. Jackson, and J.D. Haas, Microscopical morphology of the human placenta and its effect on oxygen diffusion: a morphometric model. Placenta, 1986. 7: p. 121-131.

19. Smith, A.S., et al., Placental chorangiosis associated with markedly elevated maternal chorionic gonadotropin. A case report. J Reprod Med, 2003. 48(10): p. 827-30.

20. Habashi, S., G.J. Burton, and D.H. Steven, Morphological study of the fetal vasculature of the human term placenta: scanning electron microscopy of corrosion casts. Placenta, 1983. 4(1): p. 41-56.