I am adding my notes for the SPP talk in Chicago on Uteroplacental ischemia, and the power point portion related to placental infarction.

The utero-placental circulation

A portion of the uterus underlying the implantation of the placenta must greatly increase the blood flow through its surface to meet the needs of the fetus. This is generally accepted as an 8 to 10 fold increase in flow. The simple relationship that flow is directly related to pressure and inversely related to resistance provides two potential ways to increase the flow, namely increase the pressure or lower the resistance. Increasing the pressure if done systemically is not a real option since even doubling systolic pressure would have adverse consequences on the mother, and there is no pump available to locally increase pressure in the uterus.

The natural solution in the closed circulatory system was to increase the diameter of the vessels in the arterioles of the endometrium and myometrium that supply the placenta. An approximation is that the resistance varies with the inverse of the radius to the fourth power, so a two fold increase in the radius would provide the necessary increased flow1. This vascular dilatation was demonstrated graphically by india ink in 3D reconstructions of the spiral arteries in the uterus at different gestations2.

This vascular modification is achieved by the migration of typically multinucleated trophoblast into the endometrium, and later myometrium, that destroy the muscularis of the arteries. This process is little bit more complicated because cytotrophoblast in continuity with the basal plate cytotrophoblast undermines the endothelium3,4. Further a second arterial circulation maintains the viability of the decidualized endometrium. Some invesigators have argued that the spiral artery changes are more important for decreasing velocity of flow than increasing the volume flow of blood5.

This is obviously a very complex interaction of the fetal maternal interface. Not surprisingly, the process is not always perfectly matched to fetal needs. A failure to provide an adequate utero-placental circulation (utero-placental ischemia) has two major manifestations, a placental response, and secondarily a maternal systemic response.

The placental villous response to utero-placental ischemia

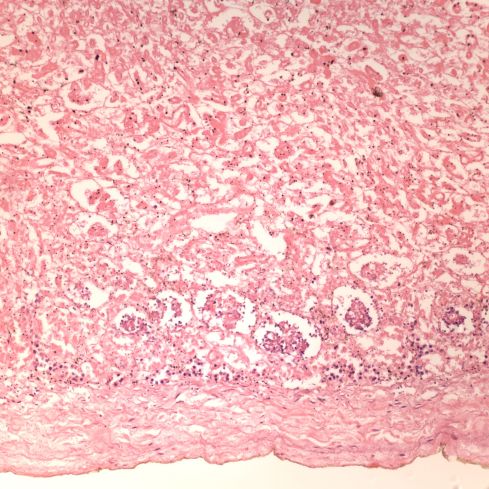

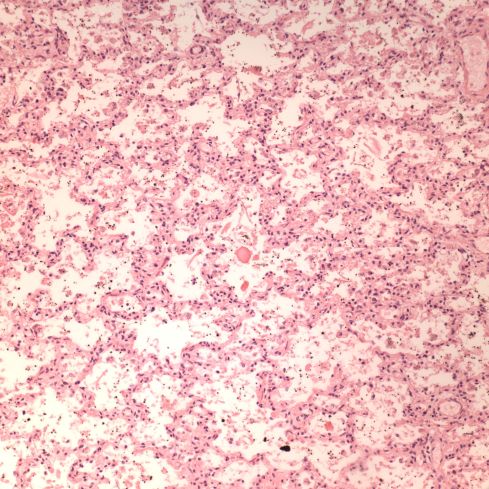

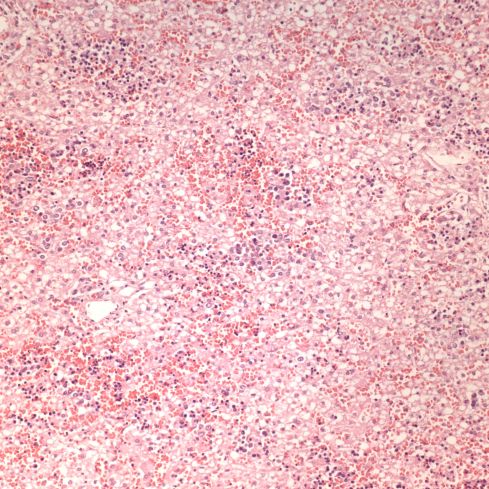

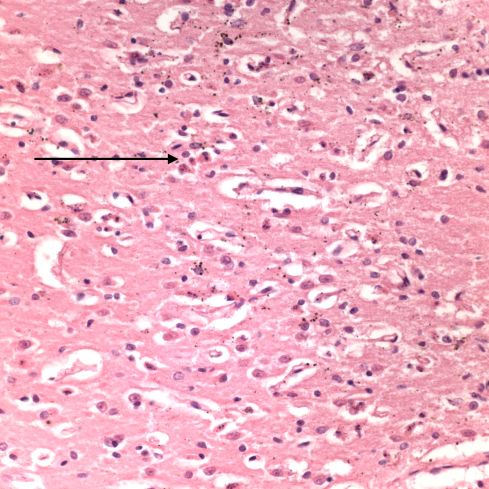

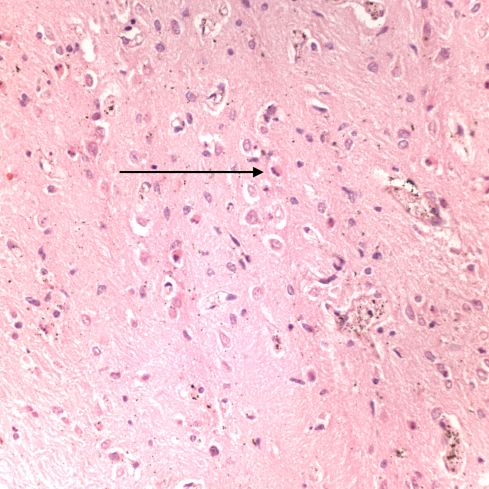

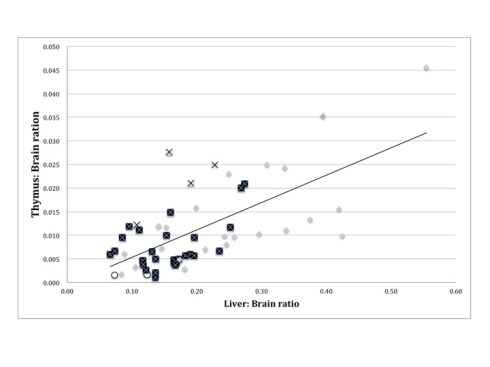

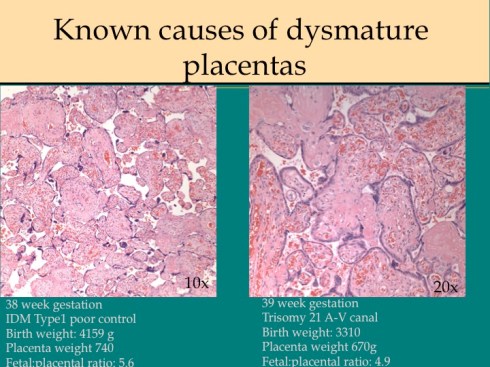

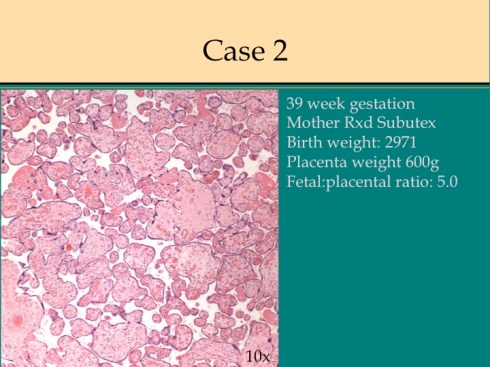

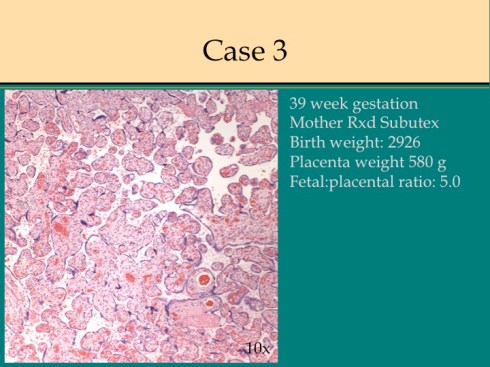

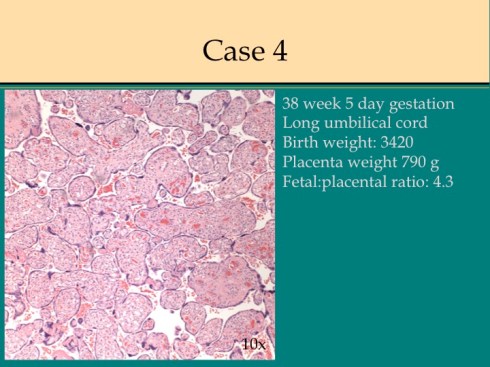

In response to utero-placental ischemia, the placenta will adapt in a way that increases the diffusion of oxygen to the fetus at the expense of nutrient transfer. This change can be looked at as the transition from areas with a more gastrointestinal type function to those with a more lung type function. This process at a less accelerated form underlies the villous changes that we as pathologists see with maturation. The immature placenta has a thick syncytial layer that is metabolically very active with transport. The mature placenta shows many capillary syncytial membranes that minimize the distance between maternal and fetal blood, much like alveolar capillaries in the lung minimize the distance between air and blood. These membranes are associated with trophoblast “knotting”, that is the clumping of apoptotic syncytiotrophoblastic nuclei that are shed into the maternal circulation. This thin barrier between the oxygen source and the capillary bed is needed for efficient oxygen transport. The actual transfer of oxygen is complicated by considerations of the fetal hemoglobin, the overall surface area, the rate and direction of blood flows etc. However, Mayhew’s group have provided a model that shows that decreasing the barrier thickness is the most important adaptation to provide the fetus with sufficient oxygen to survive in a state of decreased utero-placental blood flow6. It comes at the cost of less nutrition and therefore a proportionately smaller placenta and infant, the growth restricted infant.

This very simplified schema of placental insufficiency explains why the premature increase of capillary syncytial membranes and secondarily syncytial knots, the key to identifying utero-placental ischemia under the microscope7. This observation was perhaps first reported by Tenny and Parker, and is sometimes referred to at Tenny Parker change8. The trade off for the increased transfer of oxygen is decreased transfer of nutrients. The villous adaptation has limits, and some infants may develop hypoxia and may even die.

As a practical matter for diagnosis, the lack of villous adaptation to utero-placental ischemia in a growth-restricted infant without other compromising placental lesions is evidence for intrinsic causes of small fetal size.

The maternal systemic response to utero-placental ischemia in preeclampsia

The most common association with utero-placental ischemia based intrauterine growth restriction is severe or early preeclampsia. This is the second response to utero-placental ischemia. Medical students learn that preeclampsia/eclampsia is characterized by edema, gestational hypertension, hyperreflexia (or seizures) and proteinuria with more precise definitions available. Ideally they also learn that this syndrome can be unified as being the consequence of a diffuse endothelial injury. For example, the edema is due to capillary leakage and allows vaso-constrictive blood products to initiate arteriolar hypertension, and damage to glomerular capillaries results in proteinuria. They may also have learned that the cure of preeclampsia is delivery, although some residual effects may persist for weeks. This was the basis for old concept that the placenta was causing a toxemia. That old concept has been justified by molecular techniques that have identified substances from the placenta such as sFLT-1, which compete with endothelial growth factor and interfere with endothelial integrity9,10.

But why would the placenta secrete substances toxic to the mother in the presence of utero-placental ischemia? There is a teleological explanation. First, endothelial leakage allows vasoactive substance to reach the arteriolar smooth muscle causing constriction that increases systemic blood pressure that directly increases perfusion to the placenta. Second, leaking capillaries decrease blood volume increasing the hematocrit and therefore increasing oxygen carrying capacity of the blood. These adaptations may be sufficient to improve oxygen transfer to the infant through a short period of late gestation utero-placental ischemia. They are inadequate to compensate for more severe or earlier onset utero-placental ischemia.

There are still many questions, since other forms of utero-placental ischemia such a maternal thrombophilia with multiple infarctions do not generate preeclampsia. Of course many other forms may not create a large volume of suboptimally perfused villi. The association of a severe early onset preeclampsia with dyandrogenic triploidy suggests a more complex interaction between the placenta and intravillous perfusion than suggested in my admittedly heuristic explanation of improving fetal oxygenation.

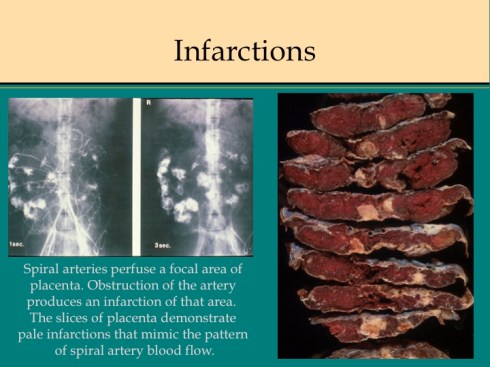

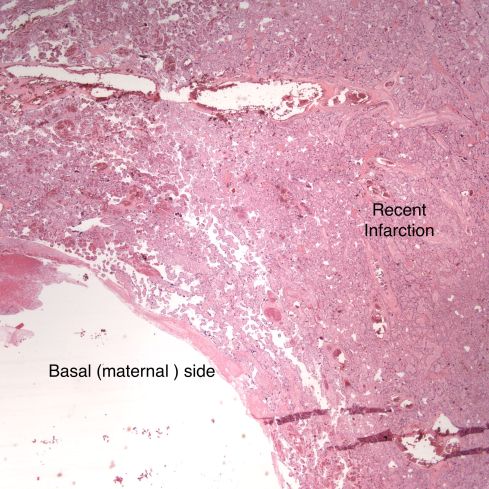

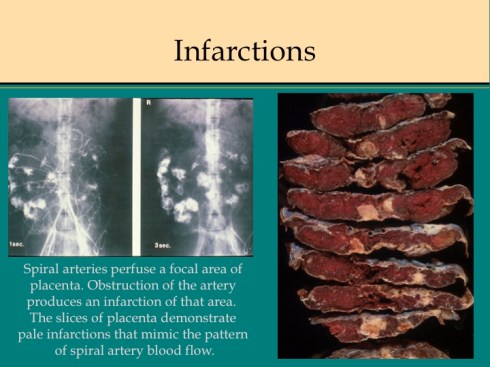

Placental infarction

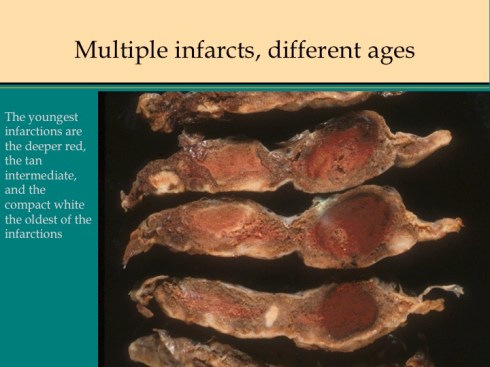

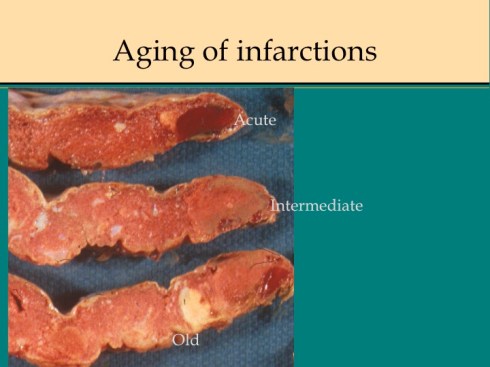

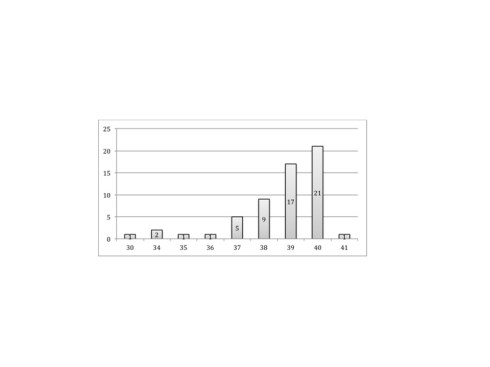

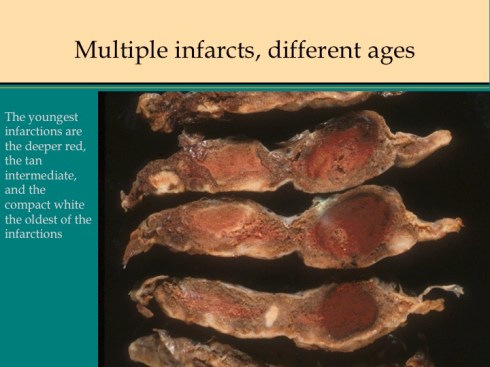

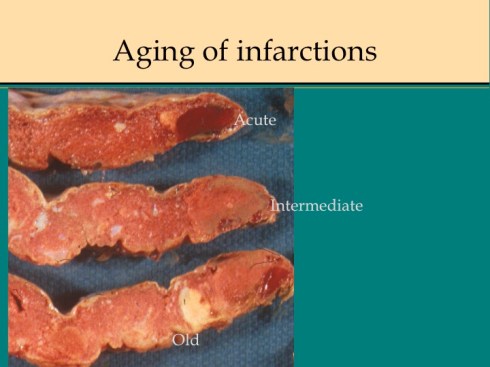

In discussing utero-placental ischemia so far, we have only considered a diffuse loss of placental perfusion. However, a fixed loss of focal perfusion can also have a profound effect on fetal oxygenation. One such lesion is a placental infarction. This is analogous to myocardial infarction in that a permanent occlusion of an end artery (the spiral artery) leads to ischemic death of the supplied tissue. Multiple placental infarctions can significantly reduce the functioning placental volume. Such infarctions occur in some patients with preeclampsia. Typically these infarctions occur at different times as evaluated by the progressive maturation of the infarction11-14. This multi-temporal dimension in preeclampsia may reflect the progressive trophoblast modification of the spiral arteries.

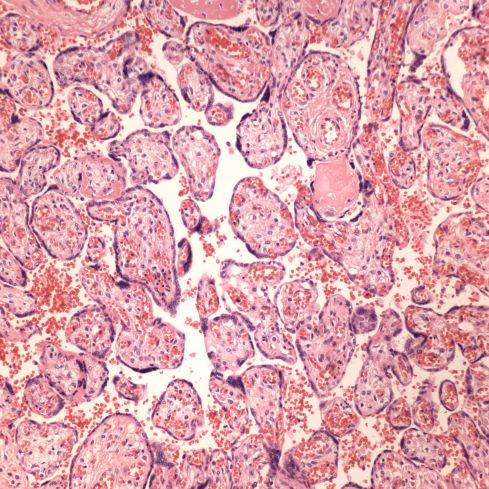

There are two ways that placental infarctions differ from myocardial infarctions because of the circulatory anatomy. First, a placental infarction differs from a myocardial in that the end artery does not occlude a defined capillary bed, but an open intervillous space where flows from adjacent spiral arteries make direct liquid to liquid contact. As we saw on Dr. Ramsey’s injections, the spiral artery flows do not really intermix despite the open space. The concept that each spiral artery has a distinct entrance zone with a central high oxygen flow and a surrounding periphery like the downward cascade of a fountain of lower oxygenated blood has been called a placentone, a persistent unit of spiral artery flow that can be seen looking at the villous morphology of a mature placenta with gradients showing more syncytial knots at the periphery, and larger more intermediate appearing villi in the center15.

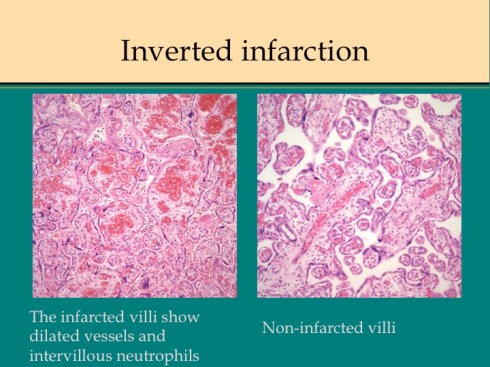

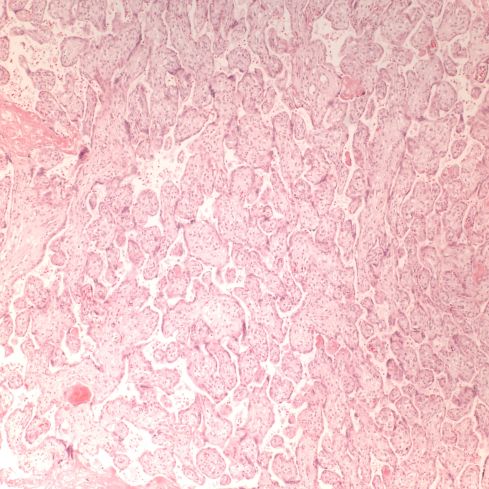

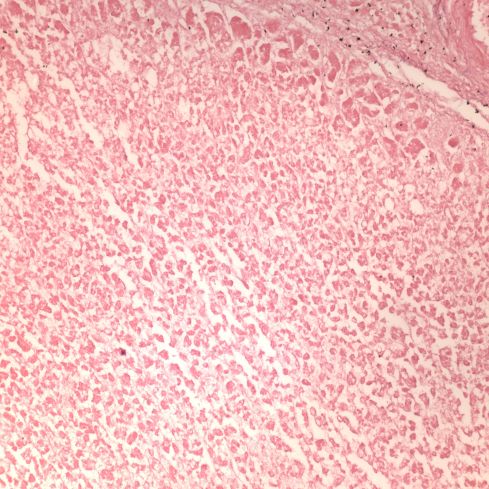

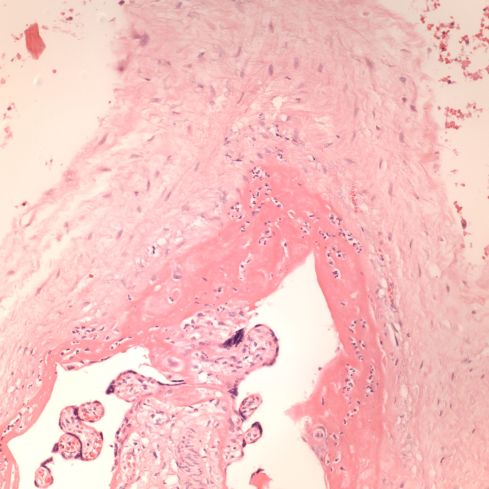

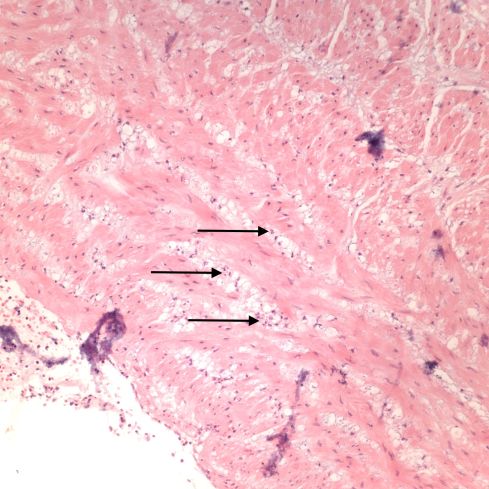

Like a myocardial infarction, an infarction would be expected to allow outside flow into the occluded placentone from collateral circulation, only in the placenta this flow would directly cross the intervillous space. As with myocardial infarctions, placentas with evidence of generalized utero-placental ischemia (analogous to coronary artery disease) tend to have larger areas of infarction than those with normal circulation. The collateral circulation might be expected to create a gradient of hypoxia around the infarction. The histologic observations seem to confirm a gradient. Typically the center shows complete coagulation necrosis of the villi. Initially there is a border of some fibrin and neutrophils like that around a myocardial infarction, but unlike the progress to scar in the myocardium, a shell of perivillous fibrinoid forms around the infarction. This can be understood if 1) the key steps of organization, with ingrowth of capillaries and fibroblasts, can not occur in the intervillous space and villi, and 2) if we accept that lower levels of hypoxia kill syncytiotrophoblast than kill the underlying cytotrophoblastic stem cells. Looking at the histology it would appear that the villous cytotrophoblast not only replenish syncytiotrophoblast but also secrete the components of fibrinoid, such as fetal fibronectin and annexins that make up the extracellular matrix of trophoblast. The hypoxic loss of the syncytium appears to result in fibrin deposition on the bare surface of the villous with stimulation of cytotrophoblast production of matrix. The next layer outward shows marked Tenny Parker changes indicating villous adaptation to hypoxia. Once again I cannot prove this gradient hypothesis, but I can offer it as a way to make sense of what you are seeing under the microscope. Even if truer explanation of placental infarction become available, they will still need to be able to explain what we see under the microscope.

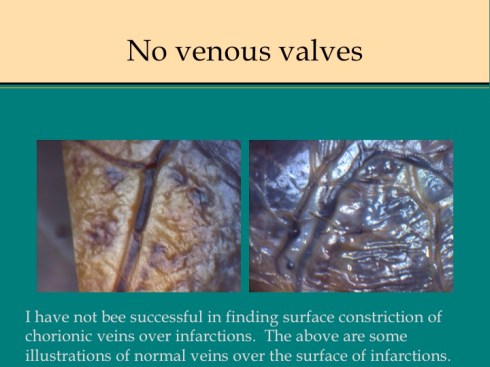

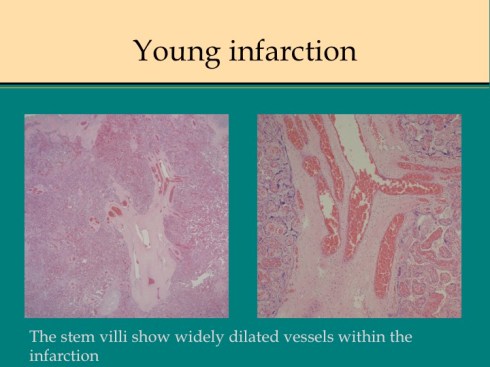

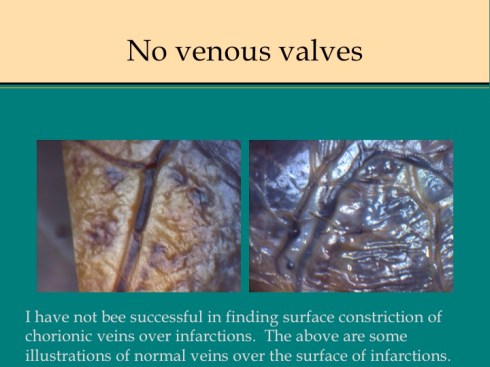

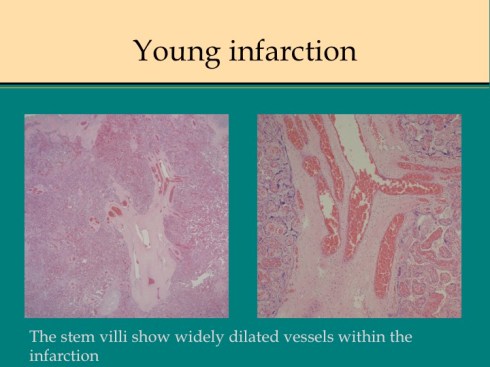

A second difference from myocardial infarction is the dual circulation of the villi. The infarction removes the oxygen supplied by the intervillous circulation, but the fetal circulation of deoxygenated fetal blood is initially still intact. As pathologists we know from observation that early placental infarctions are grossly deep red, and this is due microscopically to dilatation of the fetal vasculature. If we assume that the smooth muscle of the involved fetal vessels becomes hypoxic they might dilate under the fetal blood pressure, in which case the infarcted area would become a low pressure circulatory sink that would not oxygenate the circulation, but add potential harm from thrombogenic material potassium, etc. released from the dying villi. However, the pathologic observations do not support this scenario. There is no accumulation of neutrophils in the fetal vessels that would be expected to be chemotactic to the dying tissue, and thrombi are very rare in the involved fetal vessels. An early obstetrical theory was that placental infarctions were caused by valves closing in the chorionic veins. This theory seems to confuse cause and effect, but something like this may be happening to protect the fetal circulation16. I know of no proof of the following hypothesis, but it seems to fit the pathologic observations.

Like the lung, the efficiency of the placenta would be markedly improved if it could match the fetal circulation to the intervillous circulation, in effect optimizing ventilation to perfusion. Certainly, if the radiologic observations of Elizabeth Ramsey in monkeys are true for the human, spiral artery flow is intermittent, and the placenta would need to efficiently adapt to this variable flow. Constriction of stem vessels would be one way to do this, and indeed these are very muscular vessels, but interestingly unlike vessels in the body there is no clear histologic difference between veins and arteries. If the intervillous circulation became hypoxic, more oxygen might be extracted by slowing the villous flow and dilating the capillaries. This would occur if the villous veins constricted before the arteries. Arterial constriction would raise resistance, and fetal flow would be directed away from the poorly perfused villi. If intervillous flow were to stop as with an infarction or encasement in perivillous fibrinoid, the artery could remain constricted to the point of permanent occlusion. While this is speculation based on the observation of stopped flow and necrosis of the villous vessels in “old” infarctions, the ability of villous arteries to remain constricted has been directly observed in the lamb undergoing placental by pass for experimental cardiac surgery17. When the researchers tried to reattach the placenta to the fetal lamb, the vascular resistance was too high for the lamb to circulate. This appeared to be from arterial constriction due to vasopressin. Likewise, the umbilical arteries constrict and remain so after the cord is cut until the cord becomes necrotic and falls of the umbilicus.

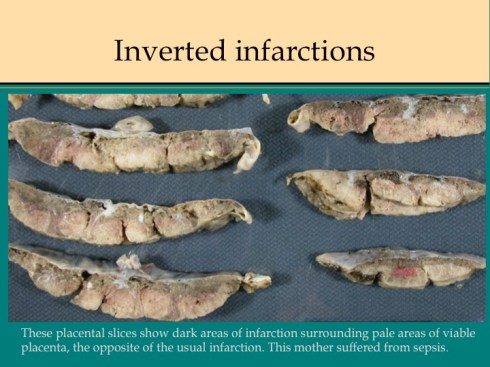

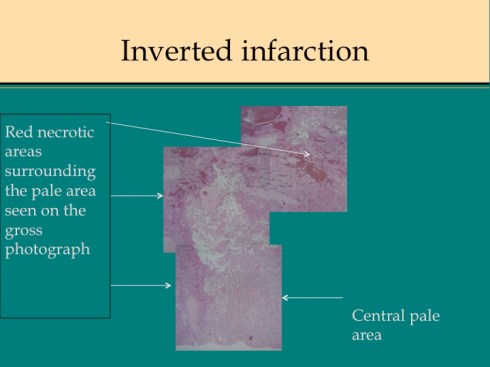

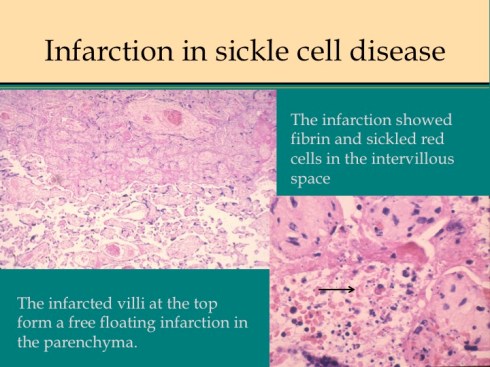

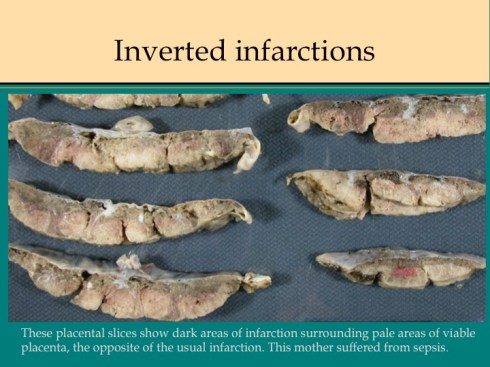

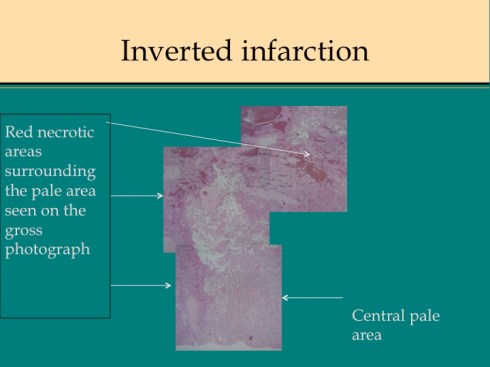

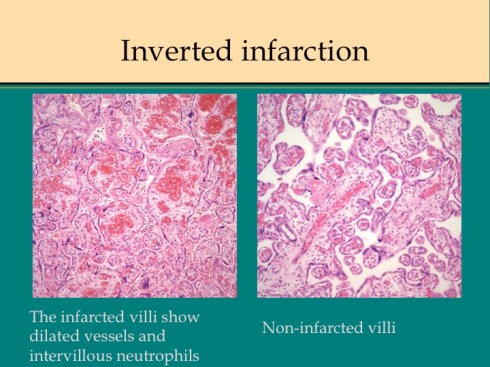

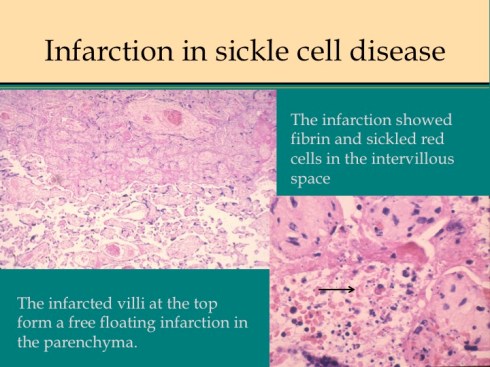

There are some other uncommon causes of infarction. If mother suffers systemic cardiogenic or septic shock, the placenta can become ischemic in such a way that the infarcted villi are at the periphery of flow rather than at the center of the placentone.18 This makes sense since the surround usually shows evidence of greater hypoxia than the center. The placentone centers are typically very pale from not only decreased intervillous flow, but also decreased fetal flow. The peripheral infarction is vasodilated like a typical early infarction. Another infrequent form of infarction is from sickle cell crisis causing thrombosis within the intervillous circulation.

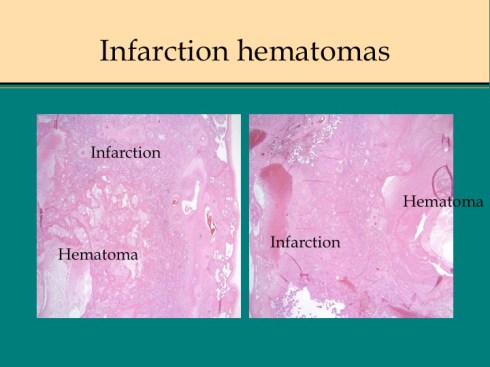

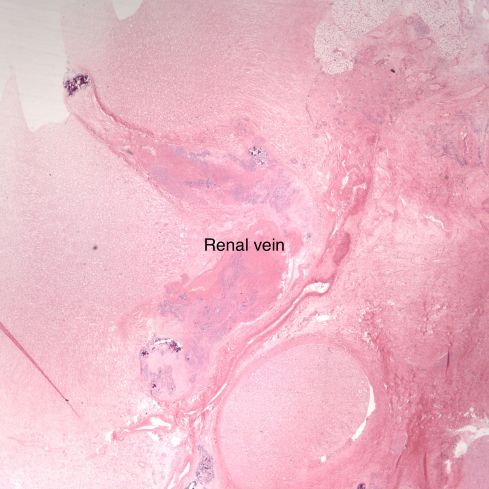

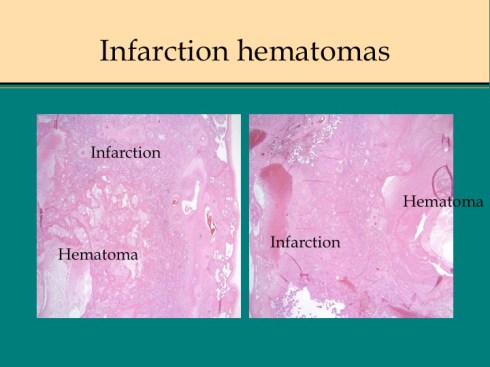

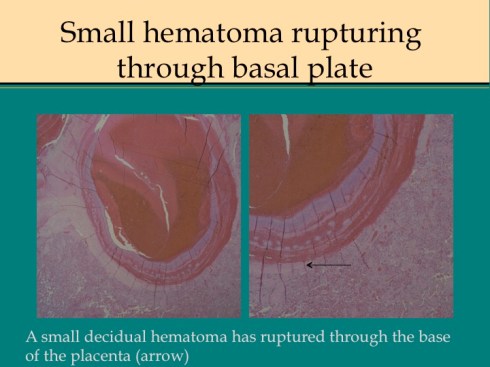

Before we leave the histology of placental infarctions, I want to point out another observation. At the base of even an old “infarction” the basal chorion and attached decidua are viable. This could only happen if the occlusion occurred distal to the separation of the basal endometrial arteries. Direct histological observation of the spiral artery underlying an infarction usually shows just stasis/clotted blood and less frequently any evidence of thrombus. The normal placental histology usually does not allow identification of the cause of the infarction. Perhaps in some cases the infarction is directly due to cellular invasion of the spiral artery or in some cases it may be from conventional fibrin thrombi. Placental bed biopsies have not solved the problem. In a few cases, maternal thrombophilia has been associated with multiple placental infarctions. The spiral artery bed may be more prone to initiating thrombi because of trophoblast remodeling than conventional arterioles adding stasis and endothelial injury to maternal thrombophilia. Some placental infarctions show a central hematoma, which appears to be hemorrhage into an infarction that could be due to either reopening of an occluded spiral artery, or perhaps anastomoses with basal endometrial arteries19.

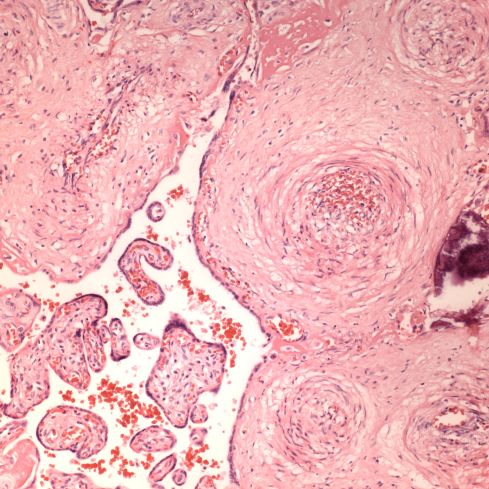

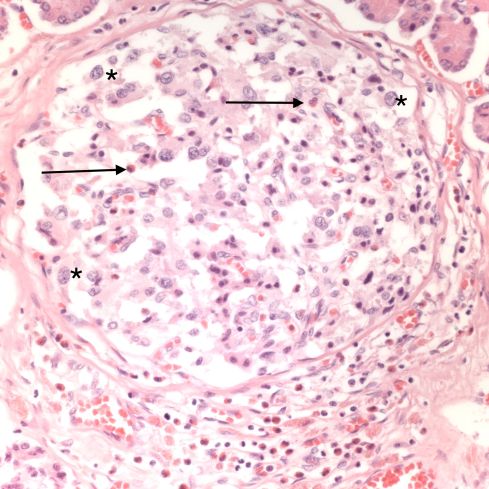

Acute atherosis

Uteroplacental ischemia, placental infarctions, and maternal capillary injury are not the only anatomic manifestations of preeclampsia. The spiral arteries not being remodeled by trophoblast, may undergo necrosis with an infiltration of plasma proteins in the wall that cause a fibrinoid appearance and insudation of lipid that results in foam cells in the vessel wall, a lesion termed “acute atherosis”20. Despite widespread endothelial injury in the body with preeclampsia, other arteries do not show this change. Examination of the fetal membranes in woman with preeclampsia show that it is a focal lesion, but appears to be absent in many woman with preeclampsia. Conversely, occasionally the lesion is present in women without any of the clinical criteria of preeclampsia. I don’t know if having the lesion has any long-term significance. Pathologists sometimes confuse the lesion with the changes of trophoblast remodeling. Acute atherosis occurs in non-remodeled arteries in the basal decidua, but the diagnosis is certainly easier in the decidua beneath the reflected fetal membranes.

Placental abruption/ premature placental separation

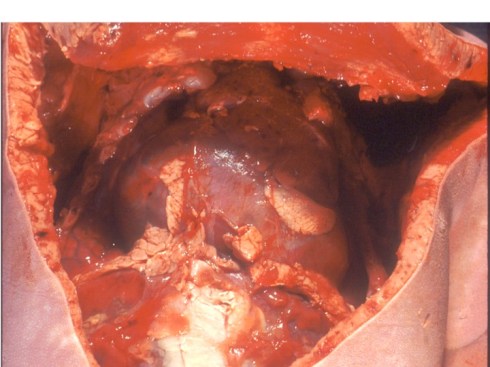

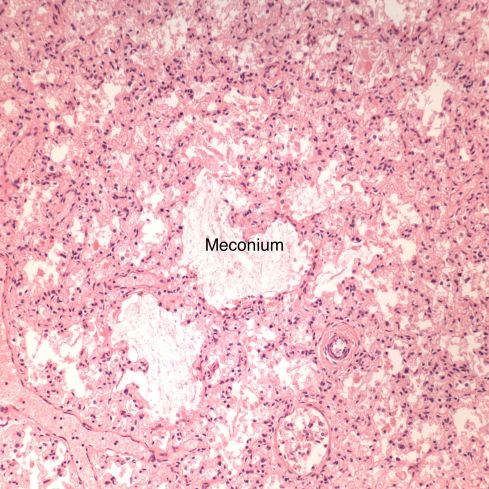

Preeclampsia is the most commonly associated risk factor placental abruption, a term that refers to the clinical presentation of separation of the placenta from the uterus prior to delivery. To understand this concept, consider that the normal mechanism of placental separation is from the shear forces of the uterine contraction after delivery of the infant and amniotic fluid cleave the decidua leaving a basal layer of endometrium in the uterus21,22. The very term decidua reflects this function as in the term deciduous leaves, and if the placenta implants on the myometrium it cannot separate with delivery, hence the term placenta accreta. A premature separation could occur if some force cleaves the decidua. Rupture of membranes in the second trimester results in proportionately more loss of intrauterine volume, and hence more contraction of myometrial area than occurs later in gestation, and may produce sufficient shear to initiate placental separation23,24. Another example of shear stress causing placental separation is the rapid deceleration of an auto accident that results in motion of the placenta in relation to the uterine wall shearing the decidua25,26. Any shearing the decidua results in tearing of the spiral arteries. If the torn area forms a closed space, blood will flow into that space from the spiral arteries until stopped by the intrauterine pressure, forming a retroplacental hematoma. If the decidua can communicate with the cervical os the blood may instead hemorrhage outward. In both cases, the intervillous space is no longer being perfused by the torn spiral arteries and the villi that had been supplied by those arteries will undergo infarction. Usually, more than one spiral artery is involved, and the contiguous infarctions from placental separation are usually larger than an occlusive placental infarction. Smaller separations may not be clinically evident, however, at some point clinical symptoms of placental abruption become evident with uterine pain and tenderness, abnormalities of fetal heart rate tracing, and maternal coagulopathy. From autopsies of stillborn infants with premature separation, a loss of approximately one half of the placenta in a single event is likely to be lethal. Smaller lesions may not have a clinically evident consequence.

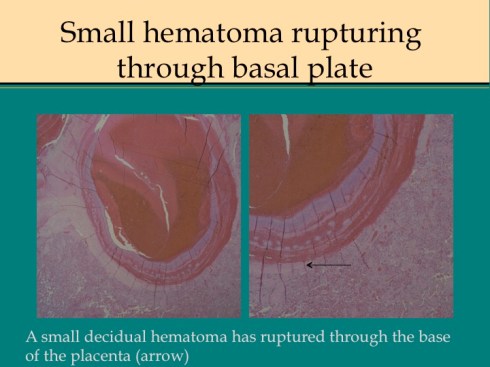

Other mechanisms of premature separation likely produce shear by an expanding hematoma in the decidua. In preeclampsia damage to a spiral could produce a hemorrhage that would have the same effect as a spiral artery torn by a shear stress with expansion of the hemorrhage in the decidua potentially shearing adjacent spiral arteries increasing the size of the mass. There is some correlation ironically of abruption with thrombophilia and it is a reasonable pathological concept that in spiral artery thrombi could leads to hemorrhage from basal artery bleeding into necrotic decidua. A similar mechanism may occur with cocaine-induced vasospasm27. Compression of the vena cava elevates uterine venous pressure and hence spiral artery pressures leading to a decidual hematoma28.

In these latter mechanisms, the hematoma appears primary, but with direct shear forces, the hematoma is secondary. The pathology does not reveal the mechanism of a placental separation, but associated infarctions may suggest preeclampsia or thrombophilia as the mechanism.

The pathologist needs to evaluate the extent of a premature placental separation at the gross examination. The placenta may still have an adherent hematoma on the maternal surface. Sometimes only the indentation of the hematoma with a craterous appearance will be found. As the hematoma ages, the color will go from red to brown to tan as hemoglobin becomes deoxidized and leaches out. At the same time the overlying infarction will similarly age. The full extent of the infarcted placenta may not become evident until cut slices of the placenta are looked at. By combining the extent of the compressed intervillous space/visible infarction, the full extent of compromised placenta can be estimated. Determining the approximate or relative age of the separation and overlying infarction may also help explain the clinical events. In a very acute clinical abruption, there may be no evidence of an abnormal separation in pathology, even though the obstetrician observed the placenta floating on a hematoma at the time of emergency Cesarean section. By a few hours of age, neutrophils can usually be found within the basal plate of the placenta. The overlying intervillous space is likely to show collapse. The infarction will progress through the same changes as with spiral artery occlusion. The blood clot will gradually become brown and then begin to lose color.

Smaller placental separations can be distinguished from infarctions by the necrosis of the basal plate of the placenta and attached decidua. In general there will also be some hemorrhage within the attached decidua. Intravillous hemorrhage may be increased above an placental separation.

Effect on the fetus

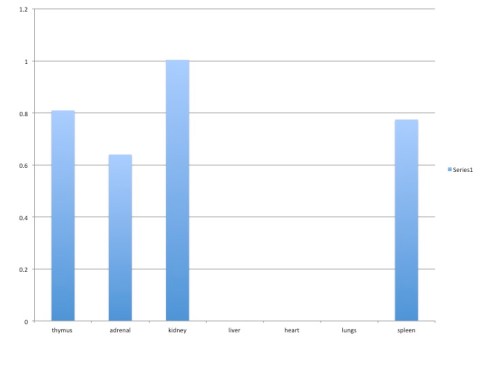

Uteroplacental ischemia leads to adaptation of the placenta that architecturally favors oxygenation over active nutrient absorption. This can eventually result in intrauterine growth retardation. If the utero-placental ischemia becomes more extreme, in theory the adaptive ability of the placenta can be exceeded and the infant becomes hypoxic. This can result in feed forward loop with hypoxia decreasing cardiac efficiency in term increasing fetal tissue hypoxia until fetal acidosis and death occurs. In reviewing stillborn autopsies, I found that stillbirths in growth-restricted infants usually had not just villous adaptation to ischemia but also placental destructive lesions such as infarctions, smaller placental separations or some other lesion such as massive pervillous fibrinoid or massive chronic intervillositis. (see abstract below) A placental separation alone could cause a subacute fetal death if it involved at least 50% of the placenta, assuming no other causes of placental compromise29. Near complete separations not surprisingly showed fetal changes of acute asphyxia. Isolated placental separations of less than 20% demonstrated no long term ill effects30.

- Vogel S. Life in Moving Fluids. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1994.

- Ramsey EM, Donner MW. Placental vasculature and circulation. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Company Ltd; 1980.

- Whitley GS, Cartwright JE. Cellular and molecular regulation of spiral artery remodelling: lessons from the cardiovascular field. Placenta 2010;31:465-74.

- Harris LK. IFPA Gabor Than Award lecture: Transformation of the spiral arteries in human pregnancy: key events in the remodelling timeline. Placenta 2011;32 Suppl 2:S154-8.

- Burton GJ, Woods AW, Jauniaux E, Kingdom JC. Rheological and physiological consequences of conversion of the maternal spiral arteries for uteroplacental blood flow during human pregnancy. Placenta 2009;30:473-82.

- Mayhew TM, Jackson MR, Haas JD. Microscopical morphology of the human placenta and its effect on oxygen diffusion: a morphometric model. Placenta 1986;7:121-31.

- Redline RW, Boyd T, Campbell V, et al. Maternal vascular underperfusion: nosology and reproducibility of placental reaction patterns. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2004;7:237-49.

- Tenney Jr. B, Frederic PJ. The placenta in toxemia of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1940;39:1000-5.

- Maynard SE, Min JY, Merchan J, et al. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. J Clin Invest 2003;111:649-58.

- Levine RJ, Lam C, Qian C, et al. Soluble endoglin and other circulating antiangiogenic factors in preeclampsia. N Engl J Med 2006;355:992-1005.

- Wallenburg HC, Hutchinson DL, Schuler HM, Stolte LA, Janssens J. The pathogenesis of placental infarction. II. An experimental study in the rhesus monkey placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1973;116:841-6.

- Wigglesworth J. Morphological variations in the insufficient placenta. J Obstet Gynecol Br Comwlth 1964;71:87184.

- Fox H. The significance of placental infarction in perinatal morbidity and mortality. Biol Neonat 1967;11:87-105.

- Wentworth P. Placental infarction and toxemia of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1967;99:318-26.

- Schuhmann RA. Placentone structure of the human placenta. Biblthca anat 1982;22:26-57.

- Bartholomew RA, Colvin ED, Jr WHG, Fish JS, Lester WM, Galloway WH. Criteria by which toxemia of pregnancy may be diagnosed from unlabeled formalin-fixed placentas. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1961;82:277-90.

- Lam CT, Sharma S, Baker RS, et al. Fetal stress response to fetal cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;85:1719-27.

- Bendon RW, Cantor DB. Stillbirth due to placental hypoperfusion after salpingo-oophorectomy for an ovarian cyst. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:482-4.

- Bendon RW. Nosology: infarction hematoma, a placental infarction encasing a hematoma. Hum Pathol 2011.

- Khong TY. Acute atherosis in pregnancies complicated by hypertension, small-for- gestational-age infants, and diabetes mellitus. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1991;115:722-5.

- Deyer TW, Ashton-Miller JA, Van Baren PM, Pearlman MD. Myometrial contractile strain at uteroplacental separation during parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;183:156-9.

- Krapp M, Katalinic A, Smrcek J, et al. Study of the third stage of labor by color Doppler sonography. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2003;267:202-4.

- Gonen R, Hannah M, Milligan J. Does prolonged preterm premature rupture of the membranes predispose to abruptio placentae. Obstet Gynecol 1989;74:347-50.

- Vintzileos A, Campbell W, Nochimson D, Weinbaum P. Preterm premature rupture of the membraes: a risk factor for the development of abruptio placentae. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1987;156:1235-8.

- Aitokallio-Tallberg A, Halmesmaki E. Motor vehicle accident during the second or third trimester of pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1997;76:313-7.

- Rogers FB, Rozycki GS, Osler TM, et al. A multi-institutional study of factors associated with fetal death in injured pregnant patients. Arch Surg 1999;134:1274-7.

- Acker D, Sachs BP, Tracey KJ, Wise WE. Abruptio placentae associated with cocaine use. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1983;146:220-1.

- Mengert WF, Goodson JH, Campbell RG, Haynes DM. Observations on the pathogenesis of premature separation of the normally implanted placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1953;66:1104-12.

- Bendon RW. Review of autopsies of stillborn infants with retroplacental hematoma or hemorrhage. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2011;14:10-5.

- Bendon RW, Coventry S, Bendon J, Nordmann A, Schikler K. A follow-up study of lympho-histiocytic villitis and of incidental retroplacental hematoma. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2014;17:94-101.